A New Industrial Revolution

How 3D printing can truly change the way we produce, distribute and consume

This article is from the archive of Roca Gallery. It was first published in March, 2023.

One machine to create any object, with infinite formal possibilities, built in thin air and emerging at any time, from your own home … That was the main promise of 3D printing a decade ago, and certainly in many cases that is indeed already a reality. Today we produce all kinds of small objects using 3D printing, not only toys or homeware articles, but also jewelry, clothing, footwear, prosthesis, or even food or organs for transplants.

As designers, 3D printing allowed us to build shapes previously inconceivable, create objects of extreme intricacy with details only present in those times when artisans were still widely available and handcrafting was not yet eclipsed by industrial manufacturing. It’s common to experience over-fascination when we have access to a technological leap, and it could not have been otherwise when we got our hands on a 3D printer.

We couldn’t stop exploring the formal complexity that we could finally materialize, hence the first arrival of this technology to the design field focused on formal expression, on the extreme detail and limitless resolution that one could finally construct. 3D printed sculptures and design objects started to populate museums and galleries worldwide, and the discourse about the possible future that 3D printing and additive digital manufacturing could bring became a must in every architecture or design school.

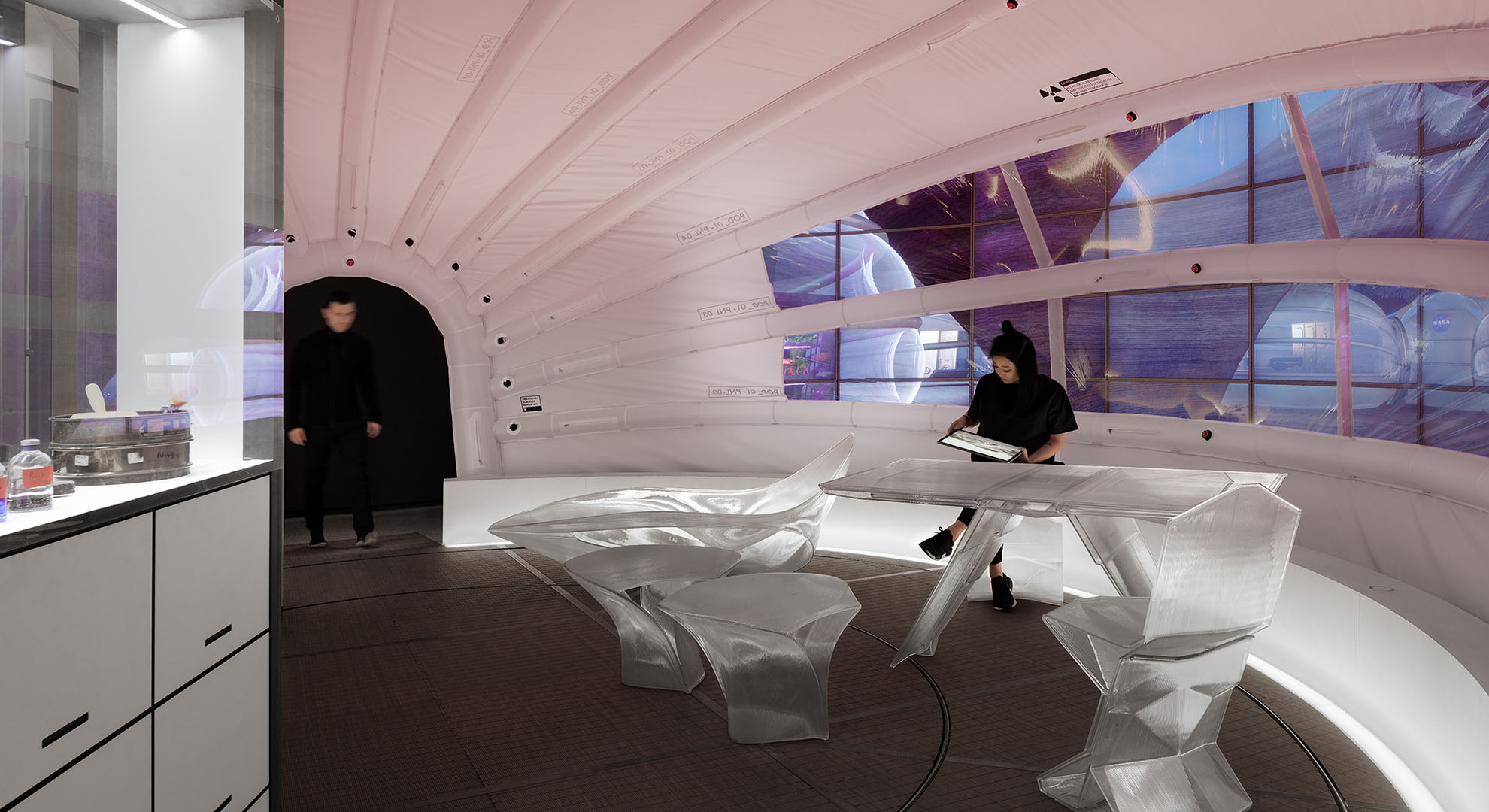

Moving to Mars, exhibition at the Design Museum, London, 3D printed furniture by Nagami, Capsule Design by Hassell Studio. Photo © Naaro

However, as good as building more and more complex forms were positive for the evolution of the technology and our design thinking around it, the real potential remained hidden until very recently, when the design community as well as a much wider industrial landscape started to acknowledge 3D printing not only as the ultimate tool for limitless variability, but mainly as the perfect solution for distributed manufacturing.

What is important in the statement, “One machine to create any object,” is not the formal complexity of the object itself, but the incredible versatility that this brings to an industrial setup, since being able to jump from the creation of an object to a completely different one in a matter of seconds implies eliminating the necessity to hold stock while allowing customization at no extra cost. We can finally design in a distributed manner, with an incredibly compact technology that gets the producer closer to the consumer, drastically reducing the carbon footprint implicit in long-range shipping, and upcycling an unfortunately abundant material source: plastic.

The need for this proximity to the source of production and quick adaptability became evident with COVID-19, when in less than one week everyone realized that the supply of medical equipment to fight the virus, especially PPE (personal protective equipment), was simply not enough to satisfy the rapidly increasing demand. Given that China—where most medical equipment is produced and exported worldwide—was under a full lockdown, and there was a complete halt of production, alternative manufacturing methods had to be found. The versatility of 3D printing allowed makers from all over the world to start printing equipment to cover the lack of supply, donating it to local hospitals.

And just like that, the paradigm of formality implied in 3D printing was broken. The world’s urgent need for agile and adaptable manufacturing processes uncovered a new way of understanding, and ultimately using, a 3D printing machine. Although this shift arose from an emergency context, it demonstrated the potential of 3D printing for accessing a real market and having a role to play in disrupting the existing production chain.

Vitrus, designed by Manuel Jiménez García for Nagami. Photo courtesy Nagami

When we started Nagami in 2016, we played the game of the formal expressions that would come from pushing the technology to the limit, which was materialized in early projects such as the Voxel Chair v1.0 or even the pieces that were developed alongside other designers such as Zaha Hadid Architects and Ross Lovegrove. Nevertheless, from the outset the true ambition of the company was to create an avenue within the existing market for 3D printing products, not negating the chance of exhibiting the work in academic or artistic venues, but always seeking to operate in a competitive and affordable realm.

The real impact in any market occurs when a completely novel product can disrupt it by being not only special but also accessible and competitive. And although those pieces, and various others that we keep producing, showcase the potential of this technology to create a new formal language, this product no longer belongs only in galleries and museums, but has been optimized to be widely adopted outside those elite environments.

The Throne, designed by Manuel Jiménez García, Nagami X and developed by To.org. Photo © Dmitry Kostyukov courtesy To.org

Today we print chairs that sell for around 400 euros and we produce custom-made interiors or even facades at a competitive rate with traditional manufacturing technologies. That is the real change and potential that 3D printing can bring to the design industry, completely changing the way we design and how we produce and distribute, not only using sustainable materials and creating unique products but also rethinking their entire life cycle from the very core.

We hope that in addition to our contribution, the effort that many others are making to expand this technology will help to finally make a change and will contribute to the real emergence of these new methods in evolving the way we produce, distribute and consume for everyday needs.

Main image: Nagami Factory, Ávila, Spain. Photo courtesy Nagami

Voxel Chair v1.0 Designed by: Manuel Jiménez García and Gilles Retsin Fabrication support: Nagami and Vicente Soler