Inhabiting the Threshold

Towards a common world

When designing, architects must envision not just an ideal society or inhabitant, but also consider how their designs can promote ideals of coexistence and community. Only through this approach can architecture with genuine relevance and transformative potential emerge.

Juhani Pallasmaa, Habitar (Editorial Gustavo Gili, 2016)

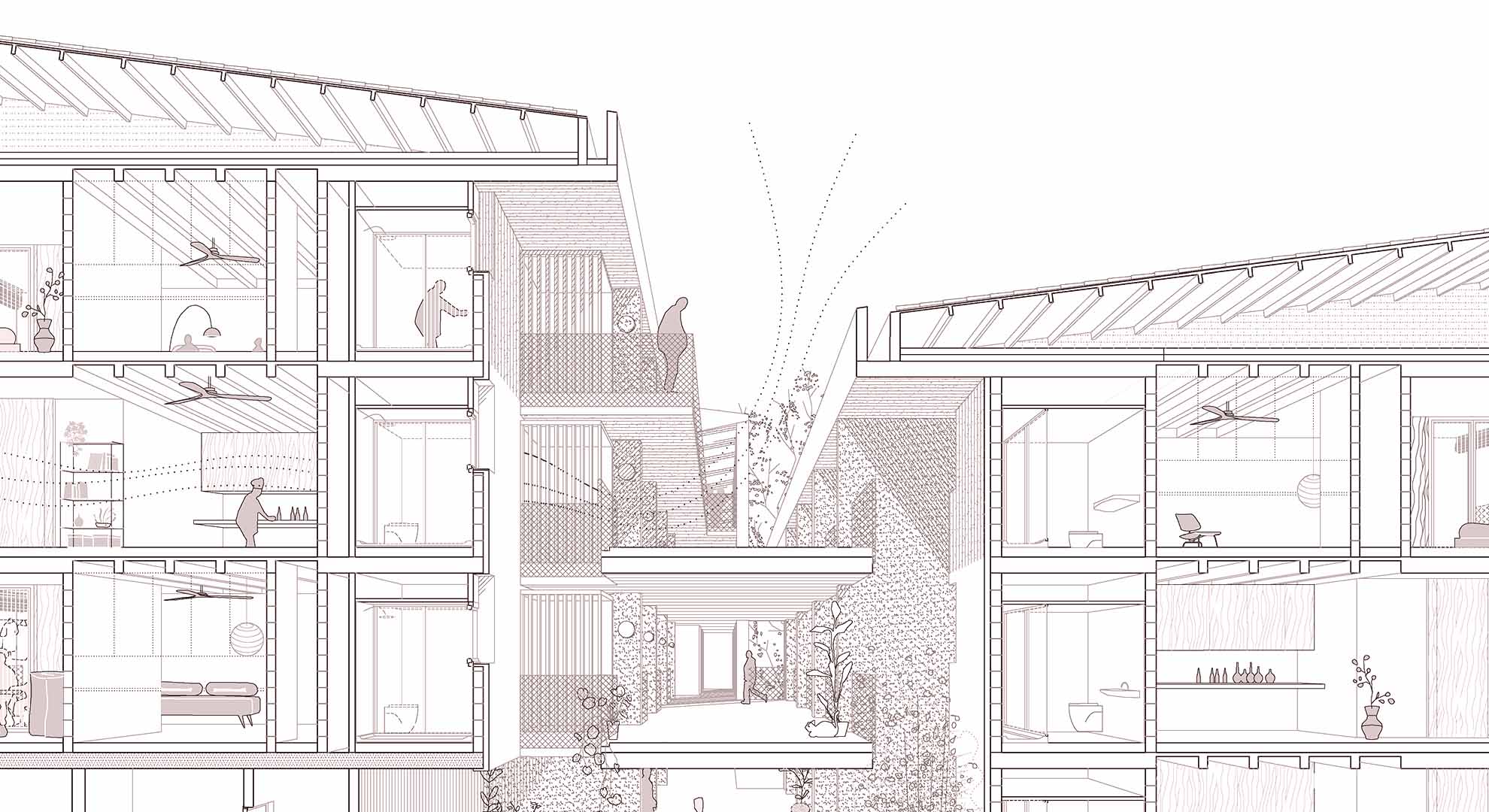

Among the verbs redefining how we live within the realm of sustainable architecture is the action of “fluffing up” buildings, extending beyond mere compliance with industrial hygiene regulations. This approach has evolved into a powerful environmental strategy, utilizing bioclimatic intermediate spaces to minimize energy consumption. The void, previously viewed as the negative of the built space, now possesses its own characteristics and is designed with the same attention as solid structures, albeit governed by different principles, the laws of thermodynamics. Today, we can measure, quantify, and simulate the behavior of fluids and analyze different parameters to achieve hygrothermal, acoustic, and environmental comfort.

It is an active void that, strategically located in relation to the building's flows, also provides a social return. Situated near inhabited areas, these spaces foster sociability instead of anonymity. They function as “social condensers,” offering the potential to alleviate loneliness and isolation.

Living in Lime, Peris+Toral arquitectes, Image © Peris+Toral Arquitectes

On the other hand, in the face of an anticipated shift in urban mobility, the idea of eliminating underground parking in residential buildings is gaining feasibility. This scenario presents the chance to “renaturalize” these active voids by introducing plants and trees that not only enhance air quality but also take root and grow directly into the ground. This approach contributes to improving well-being and mental health by promoting contact with life and nature, recognizing these elements as crucial factors for people's overall health. Rethinking circulation spaces as biophilic environments alters the perspective: they are no longer areas we need to maintain but spaces that actively contribute to our well-being.

Architects practicing sustainable architecture have long recognized the significance of gradients in intermediate spaces, viewing them as a means to slow down the pace of life and transition from the energetic urban yang to the tranquil yin of home. However, the optimization of circulation and the reduction of maintenance are parameters that have historically been key considerations in collective housing projects. The introduction of new variables such as biohabitability and the nZero consumption targets outlined in the 2030 Agenda are reshaping the context. What was once almost utopian is now a relevant question.

These new environments invite us to rethink the concept of a dwelling from its internal boundaries. If we acknowledge that language influences and shapes our thoughts, a preliminary step in reevaluating the entrance of a dwelling involves reconsidering the notion of "private" in the lexicon of the home. The etymological roots of "private" from the Latin privatus, derived from privare, carry negative connotations such as “separate,” “isolate,” “to divest of,” or “to deprive of” public use, transforming it into an individual and exclusive entity. In contrast, the term “proper” is more linked to the person than to possession, suggesting ideas of suitability, timeliness, adjustment, and convenience. While “private” implies an exclusionary dichotomy between the common and the private, “proper” hints at a more inclusive and ambiguous intermediate sphere.

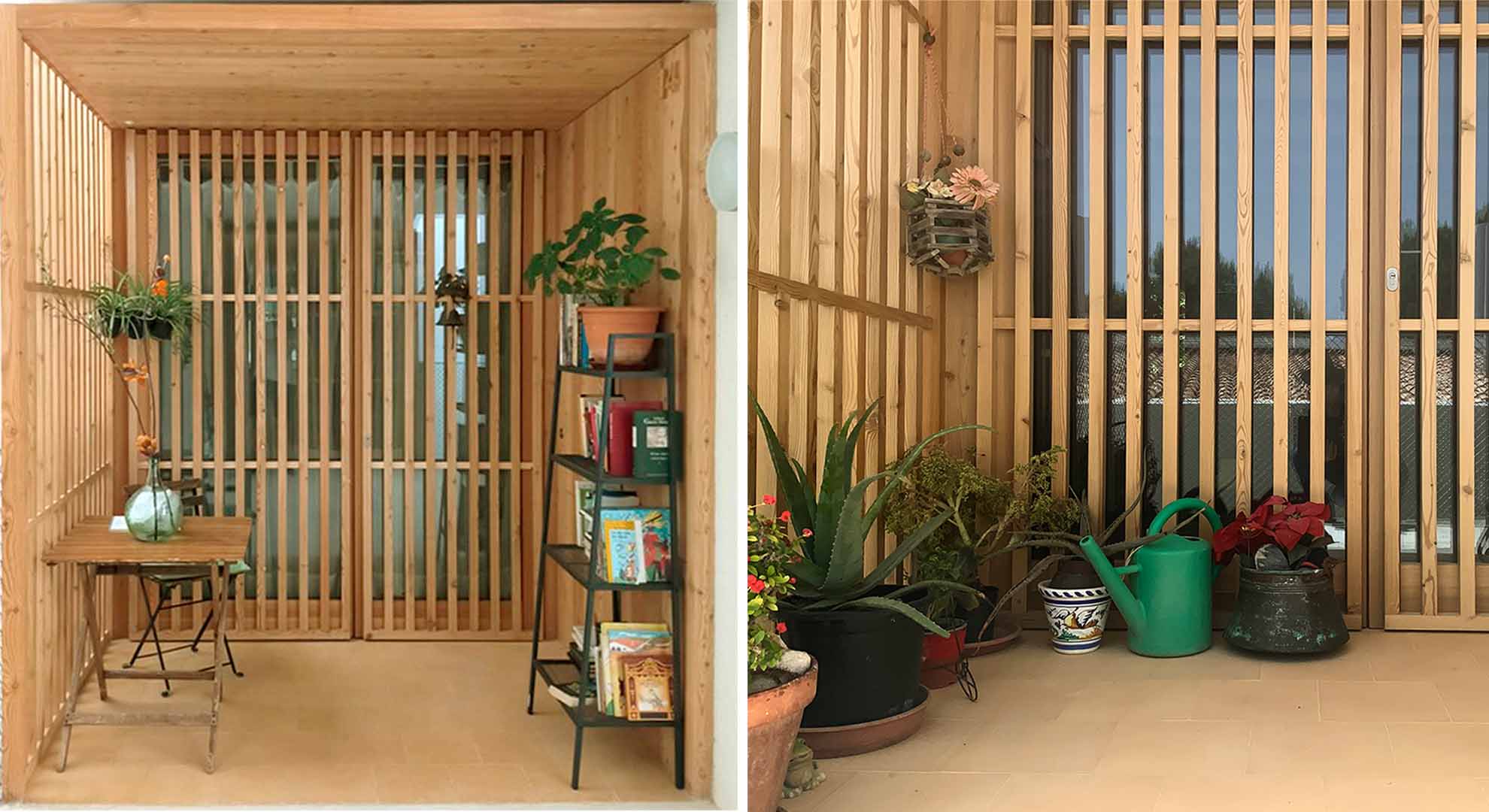

Living in Lime, Son Servera social housing, 42 units, Peris+Toral Arquitectes. Photos © Marta Peris

Rather than imposing impenetrable boundaries, doors can transform into thresholds. These small, adaptable, and customizable spaces not only reveal the lives and identities of inhabitants but also tap into our innate instinct of territoriality as a species. They serve as a zone of activity that others respect as a necessary distance, yet under these conditions, it can be permeable to both sight and air. The aim is not to dissolve the boundary but to extend it, creating another form of “fluffing up” on a different scale: a lived-in bubble where the home expands or contracts according to the inhabitant's preference. In fostering a comfortable environment, this design promotes the development of neighborly connections and interdependence, helping to alleviate the isolation and unintended loneliness often stemming from the prevailing paradigm of individualism and self-sufficiency in our society.

Shared spaces pose a notable social challenge, given the inherent risk of conflict stemming from diverse needs and expectations in each interaction. However, certain experiences suggest that these spaces can foster constructive behavioral patterns. By making the permeability and continuity of lived spaces visible, extending beyond the interior walls of homes, a collective sense of co-responsibility emerges, shifting from the idea that the common space belongs to no one to an understanding that it belongs to everyone. Witnessing everyday traces of habitation, from children's games to the simple act of caring for plants, cultivates a heightened awareness of sharing a common world. This shared dimension is gradually awakening in our consciousness.

Main image: 22@ Habitar, Peris+Toral Arquitectes, Image © Peris+Toral Arquitectes