Designing and Building a World Together

Architecture for humans and other species in a climate emergency scenario

This article is from the archive of Roca Gallery. It was first published in May, 2023.

The historical links between architecture and the world’s complexity have always been variable and not biunivocal. This looking back at the past cannot be oblivious to the fact that there are many histories and cultures on the planet, and that precisely for those most closely linked to the indigenous, the local, or the dissident, architecture and the world have always been more interwoven. In the short urban history that we can observe through the westernized spyglass, we discover humanist and mestizo periods or periods of significant disciplinary autonomy. All of them follow one after the other or mix with each other. In recent years, with the climate emergency, environmental awareness has spread, making us more conscious and responsible for what we do and its effects to live together with the world.

The links between architecture and reality address how architecture is conceived based on its use (for humans or nonhumans), on its impact on the resources that surround us (water, energy, waste, etc.), or on the ecologies in which the cities and territories we inhabit are inserted. If we focus on “who is architecture for," most of us will immediately think: "for humans." Still, a complex review of these other histories leads us to recognize a coexistence in our built environments between Homo sapiens, insects, birds, mammals, vegetables, bacteria, fungi, and other species.

Open south facade with nesting letters, connecting the indoor and outdoor track, with Belgian shepherds and kestrel. Educan, Brunete, Spain, Enrique Espinosa, Lys Villalba, 2020. Photo © José Hevia

Until a few decades ago, humans and animals lived together in urban blocks—stables, chickens, small orchards on ground floors and backyards—in cities like Madrid. In traditional architecture, the stable has always been a vital part of the thermodynamics of the home, and sources of heat and economy, such as donkeys, pigs, cows, and chickens, have been part of the extended families in rural habitats that are only a few minutes away by car from our big cities. Moreover, not far out in time and distance, sophisticated designs typical of Ottoman architecture have integrated stone, ornament, and functionality to sculpt nests in the form of miniature palaces inserted into building facades to allow the nesting of various urban birds.

More recently, from areas closer to the architectural academic world, examples show a contemporary interest in attending to this multispecies condition of our environments. In 2005, the Finnish architect Juhani Pallasmaa published a book titled Animal Architecture, which represents a change in the approach of previous studies by zoologists who had dedicated themselves to investigating the behavior of different animals and their link with their environment. For example, Karl von Frisch, whose research during the 1970s on bees was pioneering in terms of understanding their complex communication and sensory perception systems. In contrast, Pallasmaa delves deeper into animal ethology by labeling animals as "architects" in an engaging, albeit anthropocentric, view.

Detail of a nesting letter for bats with vigilant kestrel perched on top. Educan, Brunete, Spain, Enrique Espinosa, Lys Villalba, 2020. Photo © José Hevia

A leading team of architects to understand this ontological turn that allows us to speak of architecture for humans and other species is Husos (Diego Barajas and Camilo García), which for 15 years has been using architecture to explore different ways of rethinking the city from the perspective of biodiversity and ecology. Their building “Bioclimatic Prototype for a Garden Building with Host and Nectar Plants for Cali’s Butterflies" (2006-2012) is pioneering and exemplary for its design across several disciplines and its ecological approach. Husos has continued to carry out projects with these principles. However, in the last decade, the multispecies tsunami —always within a somewhat dissident and still peripheral position of a discipline not very permeable to change—has been unstoppable, including practices such as those of Joyce Hwang or Studio Ossidiana, or, in Spain, teams such as Andrés Jaque and Miguel Mesa, Takk, or ourselves.

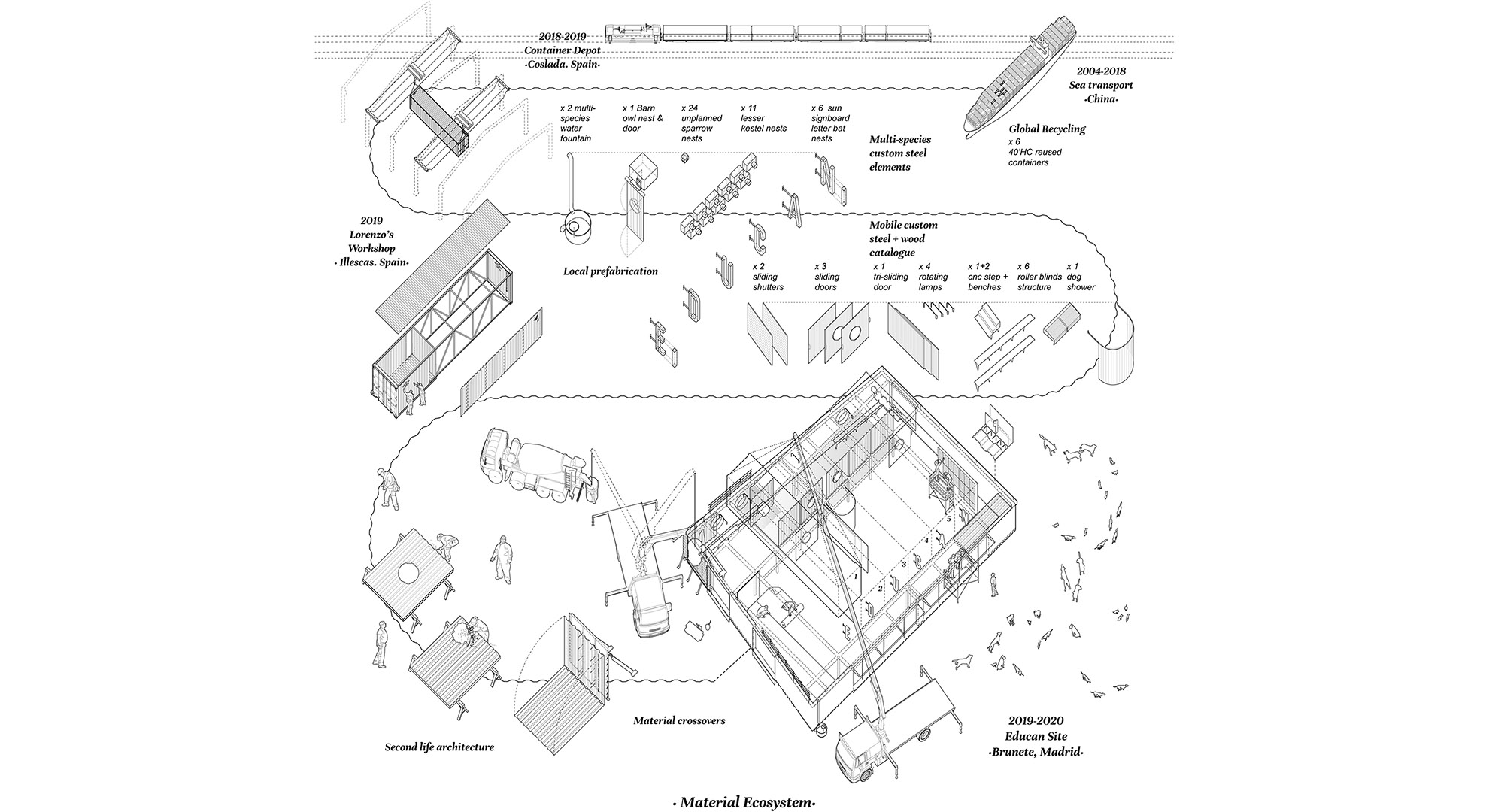

Material circularity diagram: reuse, manufacturing, and assembly. Educan, Brunete, Spain, Enrique Espinosa, Lys Villalba, 2020. Drawing © Lys Villalba, Enrique Espinosa, Irene Domínguez

Educan is a dog training center 30 km away from Madrid. From the outset, it was conceived as an opportunity to rebuild part of the ecosystemic conditions of an intensive agricultural environment that had lost much of its biodiversity in recent decades (flora, pollinating insects, rodents, birds such as owls, kestrels, or swifts). Thus, the building is based on two strategic issues. First, asking ourselves how we can design for humans, dogs, and other species, integrating nests for birds with recovering populations and bats, reusing rainwater for drinking fountains or taking care of materials suitable for the anatomy of nonhumans. Second, trying to build while minimizing the environmental footprint: reducing earthworks and energy consumption, using secondhand materials such as shipping containers, producing locally, and even reusing second and third-life resources such as the sheets of the containers that were used to build walls, form concrete walls or reclad facades of the annex building.

This is just one case within a giant constellation of small practices trying to take care of the planet, and it is not the first nor the last within a paradigm in which Homo sapiens is moving from a centralist position to one of empathic co-responsibility. Can we think that returning to other less anthropocentric architectures, more connected and interwoven with fauna and flora, can be one of the ways for our cities to "build a world" from the point of view of kindness, the environment and solidarity?

Main image: North facade with multispecies drinking trough reusing rainwater, with Belgian shepherd, after Storm Filomena in 2021. Educan, Brunete, Spain, Enrique Espinosa, Lys Villalba, 2020. Photo © Javier de Paz