A Tale of Two Abilities

Design and knowledge as the precursors to transforming the environment

Technology scares us and fascinates us at the same time. While some see it as a straight line to a utopian future, filled with benefits and well-being, others fear that unbridled technology is at best responsible for most of our current challenges, and it’s probably a burden for the future of humanity. But technology is not magic, and we don't have to be afraid of it.

We must not forget that humans are "designers by nature.” As pointed out by authors like philosopher Alva Noë—to whom I owe this term—or the cognitive scientist Daniel Dennet, this feat happened at an unknown moment some 300 million years ago, when evolution separated humans from the rest of the hominid lineage. Design is the doorway to technology, its precondition: through the use of systematic knowledge, we are capable of substantially altering the conditions given in our environment in order to transform them and make them work on our behalf.

The causes of this remarkable capacity is a combination of two characteristics, which are found in other animals, but in humans they come together in a particular and extraordinary way. On the one hand, the ability to use instruments or tools, and on the other, the ability to symbolize what we do and what we see, turning it into expressible and communicable units of knowledge.

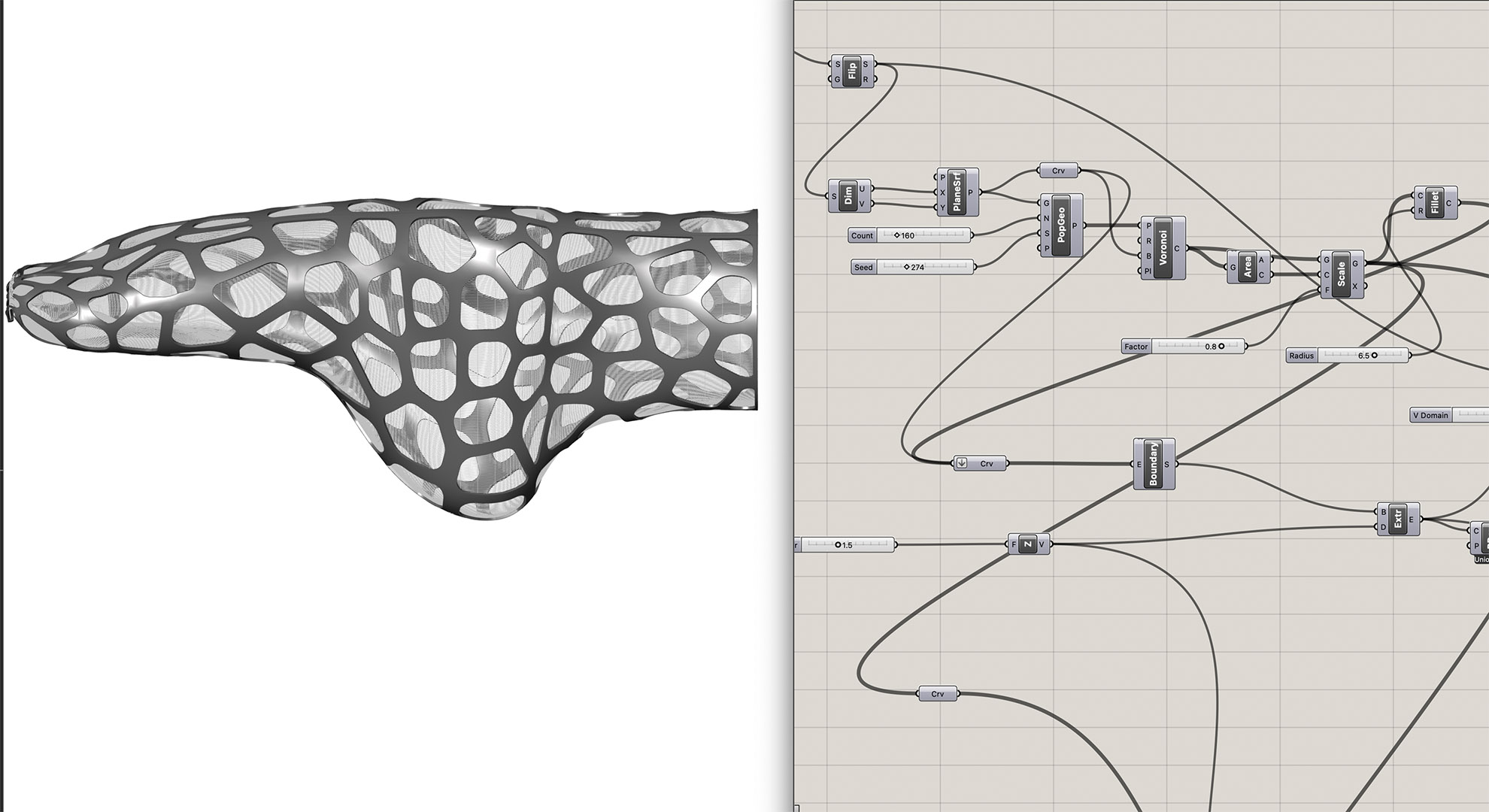

Digital rendering of a dancer's foot in Voronoi mesh, part of a research project for a parametric system to design pointe ballet shoes. Image © Marilena Christodoulou

Humans use tools, as is self-evident. The simplest tools have been sticks and stones, which are also used by other animals such as birds, fish and insects, and, very notably, by apes. But humans have a sophisticated and advanced use of tools, like knifes and weapons, pottery, shelter and buildings, cars and trains. We have reached an impressive sophistication in the use of tools, which augment, complement, protect, and allow us to do things that we could not do with our bare hands or our naked bodies.

Moreover, beyond physical tools used to increase our physical strength, we have developed tools of a symbolic type, which allow us to increase our cognitive capacities. Examples of this are numbers and mathematics, concepts and philosophy, logic and reasoning and, of course, language. The art of design and architecture is one of these symbolic aptitudes, with which humans are capable of modifying their environment for their own benefit and that of other fellow humans. This is what we call technology.

But this leads us to the second consideration regarding what separates humans (hominids) from other animals: the symbolic processing we can do with this technology. In fact, “symbolic processing” is just an imprecise, useful way of giving it a name. It’s not yet clear whether other animals communicate the use of tools to their peers, or if it is an adaptative or innate trait. We know they transmit the ability to make nests, crack nuts, weave webs, find flowers or food, or use sticks to probe holes for insects.

In humans, technology’s ultimate goal is to alter “the environment” but, in addition, it’s conceptualized, described, explained, and transferred to other humans, in a very efficient way, both with the use of language—explicit knowledge—and with imitation and learning—memes, or tacit knowledge. On a massive scale, this way of operating has given place to an extensive technological and social culture, of which the most extraordinary outcomes have been the agricultural, urban, industrial, and digital revolutions. Architecture, urban planning and design are part this technological culture, and have always evolved along with them.

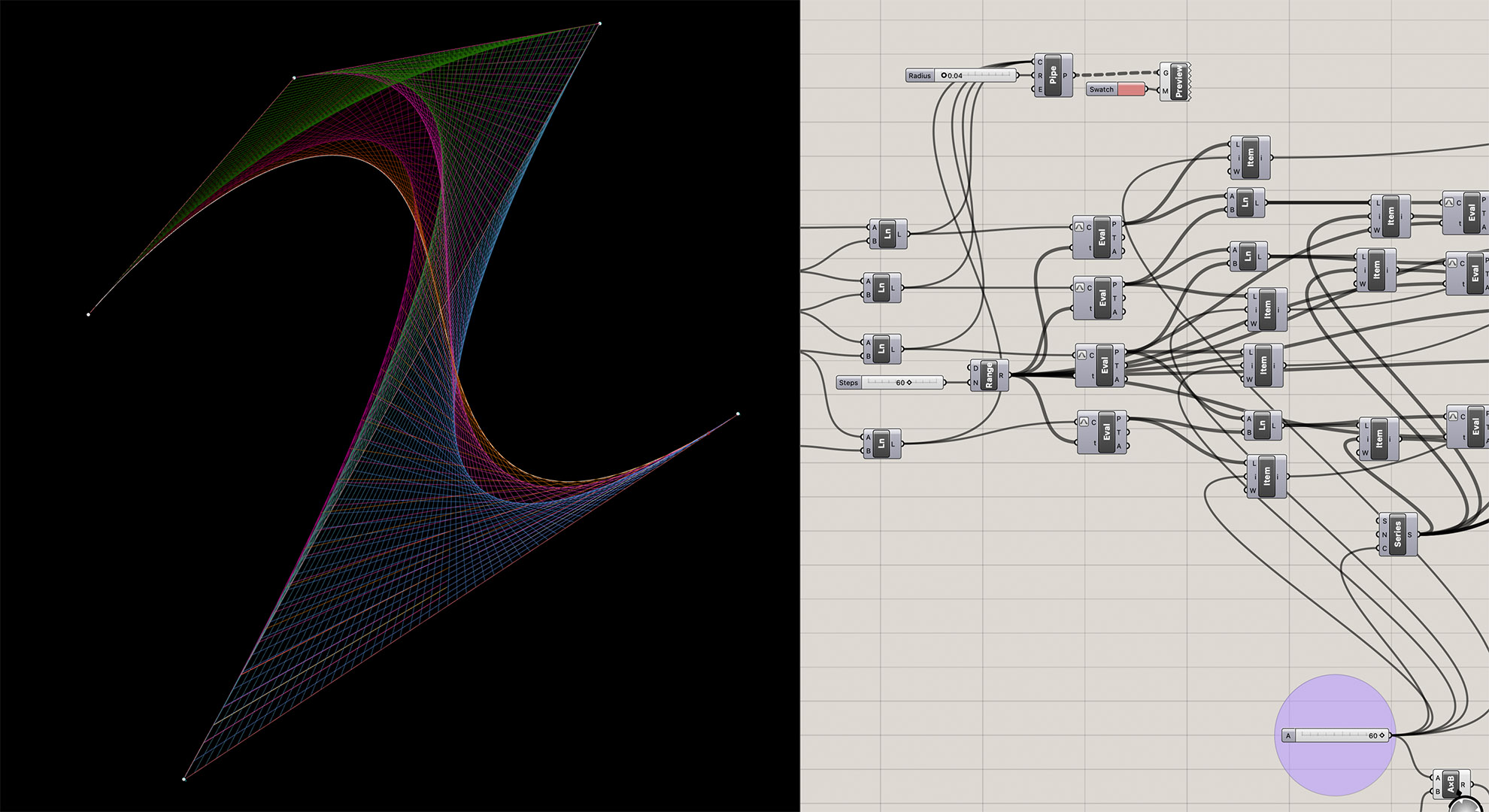

A series of Bézier curves digitally rendered with the help of Grasshopper. Image © Marilena Christodoulou

What is remarkable is the relationship between both abilities, and how they interact to create an even grander potential. The transmission of ideas, of explicit and tacit knowledge—scientific and technological culture—is precisely what gives us the stunning capacity to set new goals and, through design, create yet new technologies, new tools, new ways of interacting with the environment and modifying it to our benefit. Digital technology is just one more layer of sophistication: machines that gather, manipulate and transmit data, language—and sometimes knowledge—and are known to “learn” as long as learning is a manipulation of data and language.

It’s obvious that misuse and abuse of technology has been used to subjugate wills and force humans, and the excessive violence that has been wrecked on nature has brought us to the edge of the cliff. But the attitude of the “Luddite” is not smart either: technology is the solution. What we need to consider is: who owns and who controls technologies? And for which purposes? We must make all possible efforts to understand technologies, and demystify them to avoid the “snake oil” effect. And make all necessary adjustments to regulate them, taking the upper hand to make sure technology works for us. Because there is nothing magical about it.

Main image: A juvenile capuchin monkey using a stone as a tool to open a seed. Photo Tiago Falótico, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons