Architectural Snapshots of Memory

Photography plays a major role in architectural awareness

Photography has always had a direct and close relationship with architecture, even before it existed as such. Indeed, the representation of reality started with the birth of humanity, but it was during the Renaissance that Filippo Brunelleschi made a series of studies and experiments that allowed him to develop the mathematical and graphic method of linear perspective.

From that moment on, painters began to adopt this technique that allowed them to establish relationships within the scenes of their paintings, depicting more accurately what they observed in reality. From the 16th century onwards, portable camera obscuras were built, giving painters a new tool to help add perspective and details to their paintings. The projected image of such a device could not be fixed, but it allowed artists to perform manual ‘tracing’ or copying of reality in a precise manner. Perspective and the camera obscura were methods that, upon the arrival of photography, contributed to specific ways of seeing the city and architecture. Within this historical evolution, it can be said that photography was invented at the moment when an image could be fixed. This was achieved by Nicéphore Niépce at the beginning of the 19th century, when he produced the first photographic image. His photograph, entitled Pigeon House and Barn 1827, shows a section of architecture. Not only was it the first photograph, but it was the first architectural photograph.

From that moment on, architectural photography focussed on documenting the city and its buildings. At a technical level, perspective control was resolved with plate cameras, and with the arrival of reflex cameras, it was achieved with decentralized objectives. But with the arrival of digital and its subsequent evolution, there are photographers who perform perspective correction using software.

Technique aside, the development of architectural photography came to be a valuable tool in order to give more exposure to architecture. This process started during the first decades of the 20th century and reached its peak in the 1950s and 1960s. When it came to explaining architecture, the relationship between architect and photographer was close. The architect always resorted to the same photographer, and they worked in tandem to produce photographs that faithfully reflected what the architectural project was. A few examples of this intense relationship between architect and photographer are Eero Saarinen and Ezra Stoller, the Case Study Houses and Julius Shulman, and Le Corbusier and Lucien Hervé. The fruits of these collaborations found distribution channels in specialised magazines and books, helping to spread the image of a certain kind of architecture all over the world. This trend of sharing a ‘universal architecture’, under different names and through various evolutions, continued until the end of the 90s. Its roots could be traced to the avant-garde of the early twentieth century. Modern architecture first evolved to an ‘international style’, which eventually gave way to different architectural styles starting from the late 70s.

The aforementioned ecosystem enhanced the concept of ‘architectural icons’, making the memory of architecture very clear and precise over the years. A significant case is that of the German Pavilion for the International Exhibition of 1929 in Barcelona, executed by Mies Van Der Rohe. The pavilion was dismantled at the end of the exhibition, but its memory lasted as if it still existed, becoming one of the most referenced buildings in the field of the study of architecture. Thanks to existing photos, and a deep research, in 1986 the pavilion was physically reconstructed in the same place where it had been located decades before. Another current case in which photographs have assisted in the reconstruction of architecture is that of Casa Vicens by Antonio Gaudí. Thanks to original photos, the character and certain parts of the building have been faithfully restored. One example is the porch on the first floor, which was accurately recreated as part of the restoration work carried out by architects José Antonio Martínez Lapeña and Elías Torres.

Since the digital boom, which began in the 90s and in which we are still submerged, the scene has changed substantially.

The camera has become an accessible tool that anyone can use. This has led to the dissolution of the old scheme, and although the ‘head’ photographer continues to exist, many other photographers do reportages of the same buildings without the architect’s supervision. Likewise, people who were previously only observers now give their points of view with photographs through blogs and social networks. Many print magazines now only have a digital version, others were digital from the start. Blogs and social networks have become powerful channels of dissemination of architecture, and can immediately publish photographs from anyone, if they are of interest.

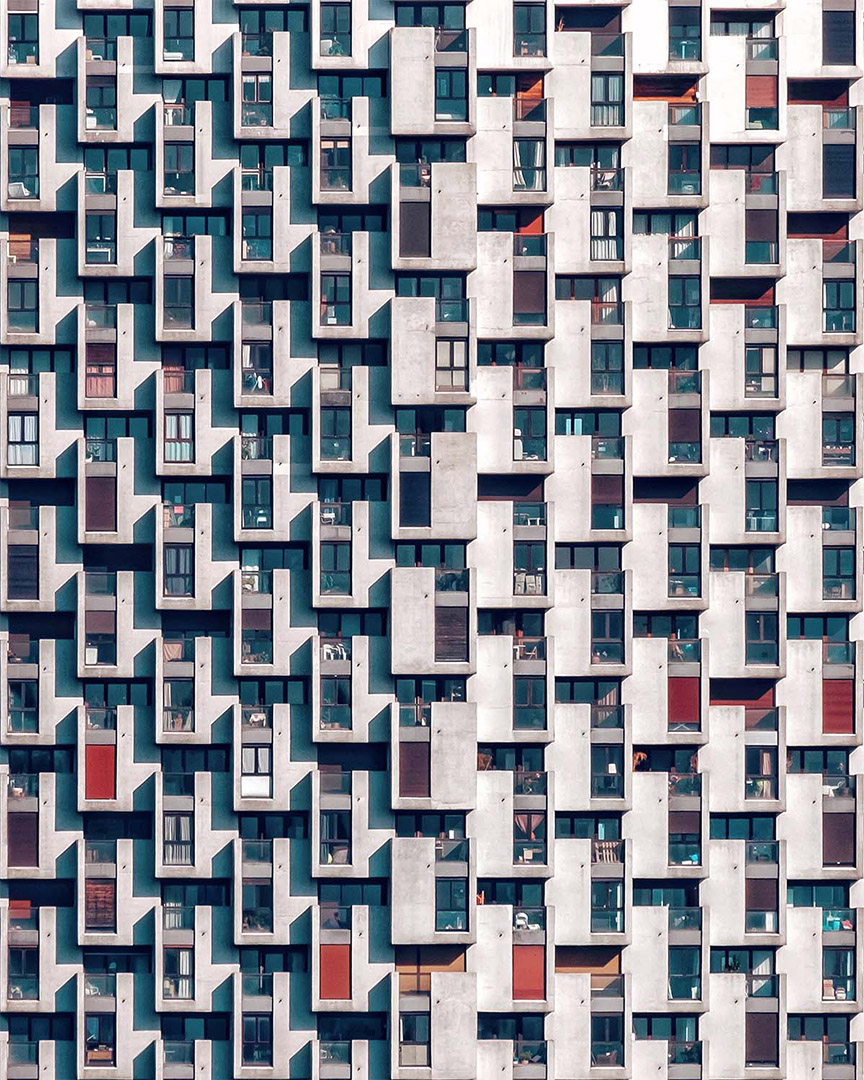

ARCHITECTURE PHOTOGRAPHY BY NICANOR GARCÍA © NICANOR GARCÍA

Although this would suggest that the documentation of the architecture would be richer and more diverse, curiously the multitude of possible photographers resorts to similar points of view, which after repeated sharing constitute the new icons of what memory will record (6). This collective intelligence then contributes to the development of artificial intelligence in all new software and devices, the sum of which is marking this intense moment of change. Despite the homogenizing effect that this evolution could have, collective memory is compensated by the immense creativity with which each one of us can contribute.

Main Image: Places & Spaces. Architecture photography by Nicanor García © Nicanor García