Autonomous Commerce is Coming for Architecture

How architecture embodies commerce and co-evolves with it

We don’t think of fast, fleeting, personal technology affecting the relatively permanent foundations of furniture, fixtures, and floorplans. But it does – and on a timeline that designers and architects need to heed. Technology is the strongest and fastest driver of those changes, and not just innovations integral to buildings themselves. Factories, then automobiles transformed city structures over the last century – and autonomous algorithms are next.

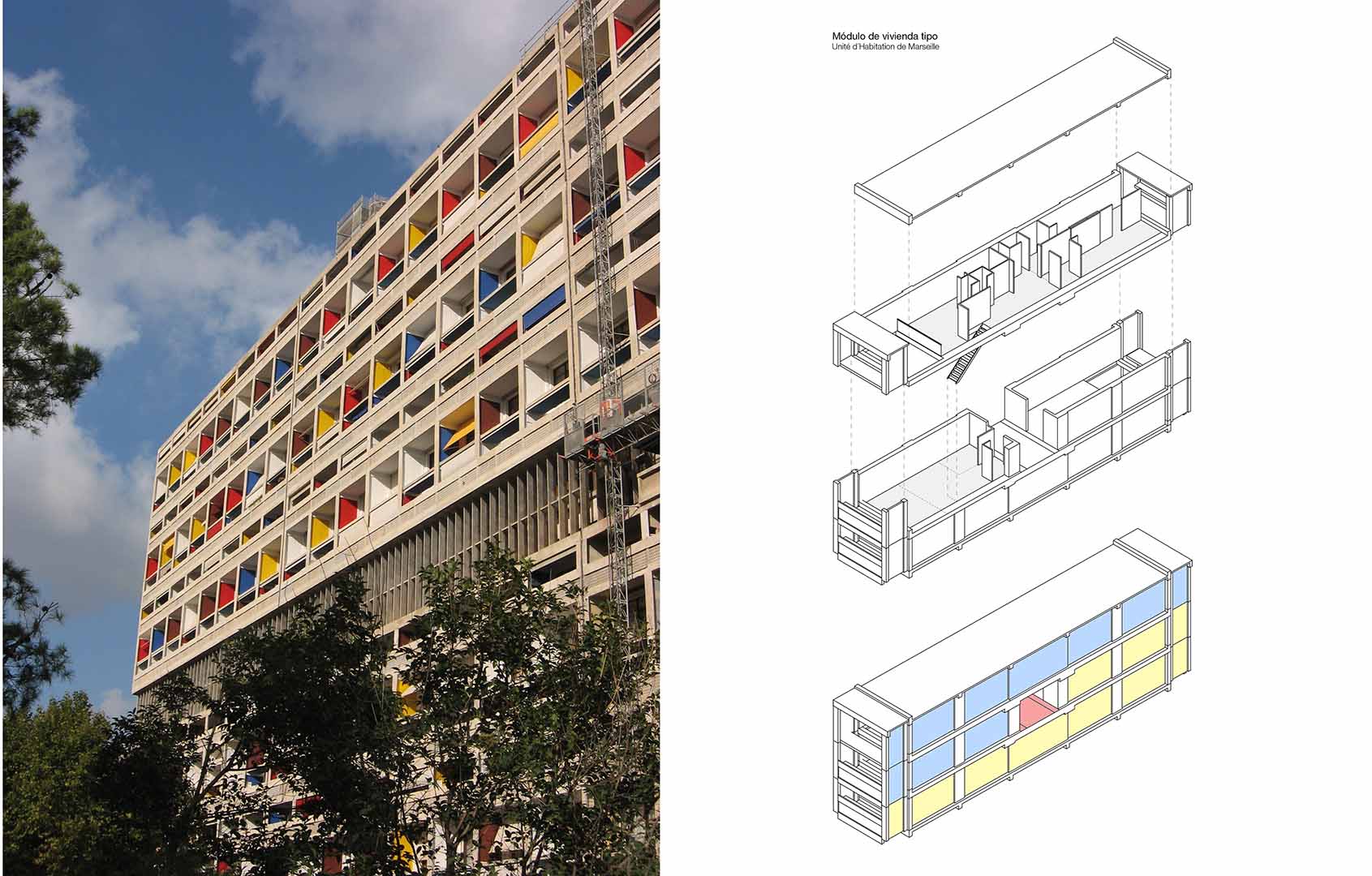

In the 1940s, booming factories attracted young families to cities. Le Corbusier envisioned Unité d’Habitation: dense, high-rise apartment buildings that embodied the new social order. Close to public transit, they didn’t need garages; small stores onsite sold food and household goods. Daily commerce cycles only required small storage spaces that featured built-in furniture, tiny kitchens, and dozens of other space-saving convenience features. The communal rooftop and park outside were shared spaces for sports, entertainment, and socialization.

The antithesis of Le Corbusier’s design is the American McMansion – giant suburban houses that rose to popularity in the 1980-90s. They had one bedroom for each household member, huge rooms dedicated to big-screen TVs, CDs and videotapes; and lawns bigger than city parks. Located far from downtown office towers, developers built eight-lane highways to access these suburbs, lining them with sprawling malls, shopping centres and hectares of parking lots. Three-car garages housed large suburban utility vehicles (SUVs) needed for the trip to Walmart and supersized boxes of enough cereal, detergent, and toilet paper to last a month or more. Garages had massive shelves and deep freezers, while SUVs took on features of homes, like entertainment centres and cup-holders.

In both cases, buildings co-evolved around a particular model of commerce. Every transaction flowed together in a self-reinforcing system that stretched from storage space in single rooms, to the layout of the city itself. The new design was immensely popular, widely copied, and emblematic of its age. But soon they symbolized everything wrong in the world: dehumanizing industrialization, and conspicuous over-consumption. Many once-gleaming block apartments are now slums, and hipster Millennials are shunning McMansions for urban lofts.

Designing Homes and Cities in The Age of A-Commerce

As disruptive as factories and cars were to commerce and architecture, digital technology is bigger and faster. If economics and architecture co-evolve, how will technology affect the future of architecture?

It was home computers and electronic commerce (e-commerce) in the early 2000s, followed by smartphones and mobile commerce (m-commerce) that changed not just how we shop, but physical spaces themselves and some concepts about architecture. Bookstores, record stores, post offices, and travel agencies are gone, and banks opened cafes to keep a profitable physical presence. Workers started telecommuting, and office spaces closed while co-working spaces opened up with more appeal to digital nomads. Hotels and cities struggle to deal with Airbnb, while its subsidiary Samara enters home design.

If e-commerce and m-commerce were already big, autonomous commerce (a-commerce) –powered by artificial intelligence, blockchain, and the Internet of Things– could prove even bigger.

How A-Commerce Will Impact Architecture: The Transaction Membrane

Where digital deals with interfaces, architecture deals with membranes: the boundaries between spaces that define interior and exterior, open and closed. Where a-commerce meets architecture, we propose the transaction membrane as the layer that admits or excludes commerce in the form of goods, people, energy, and other exchanges of value.

Homes once had separate entries for servants and delivery of groceries; a perfect model for drones and other autonomous delivery vehicles. Amazon is testing smart locks that allow package carriers to enter our houses, and sidewalk delivery robots are being tested by companies like Segway, Starship, and Serve. In order for these exchanges and transactions to happen safely, we need a transaction membrane. This could mean reinventing the foyer or entrance hall of our apartment to function as a loading dock, or smart windows and doors that open for small drone deliveries. After the robot drops off the day’s food, it could take out the day’s trash. When they’re not delivering, these drones could perform maintenance, cleaning and security tasks.

A DELIVERY ROBOT IN ESTONIA DEVELOPED BY STARSHIP TECHNOLOGIES

Like transportation, storage and appliances could form part of the membrane, transformed and embedded into buildings. A refrigerator or oven could have two openings, one inward towards the living space, and the other outward to the exterior. A-commerce will turn expensive, rarely used gadgets into a shared ‘appliance-as-a-service’ model, freeing up kitchen space.

Like appliances, the store or supermarket of the future could also become mobile – a ‘robodega’ with wheels instead of walls. Even if they do reside in buildings, the rise of object recognition and unmanned markets will entirely transform our shopping experience. Maybe we’ll make more at home: researchers estimate we could move the same amount of people and goods with 40% or even 10% as many vehicles as today. If garages empty out, they could be converted into indoor garden spaces or home recycling centres.

This transaction membrane will become the new layer of convenience about architecture, security and privacy in an a-commerce world. More importantly, it will address social and environmental issues such as the distribution of household labour, the optimization of food distribution and waste, and the integration of living, working, and shopping spaces to free our time for the enjoyment of life. Architects and designers must incorporate this new commerce paradigm from the personal to a planetary scale.

This article was co-authored by Mark Bünger, who writes with Cecilia MoSze Tham about the future of technology, design and humanity.

MAIN IMAGE: The future of retail. Illustration by Nils-Petter Ekwall