Fields of Play as Sites of Spatial Invention

The architectural side of spaces dedicated to sports

“It was all about making space and coming into space,” Barry Hulshoff, the former Ajax Amsterdam and Netherlands national football team player, explained to David Winner, author of Brilliant Orange: The Neurotic Genius of Dutch Soccer (2002). “It is a kind of architecture on the field. It is about movement but still it is about space, about organizing space.” At first instance, pairing architecture and football brings to mind stadiums, such as the sparkling new home of the Tottenham Hotspurs, but it also points to something fundamental to the game itself. We play and watch sports for many reasons. Among the attractions of physical challenges, camaraderie and the excitement of uncertain outcomes, is the generation and solution of spatial puzzles. Sports are spatial practices, and fields of play are sites of spatial invention.

“Playing a game,” the philosopher of sport Bernard Suits writes in his essay “The Elements of Sport” (1973), “is the voluntary attempt to overcome unnecessary obstacles.” Thus in golf we willingly, if sometimes maddeningly, use a club to convey a small ball into a slightly larger hole several hundred meters distant rather than carry it by hand. The devising of such unnecessary obstacles includes the construction of frames within which games are played—from kit bags marking goals for a pickup football game to the manicured pitch of a professional stadium—and the regulation of time and behavior that differentiates the social space of the game from everyday conduct: hip-checking is permissible in the hockey arena but bad form in the grocery store aisle.

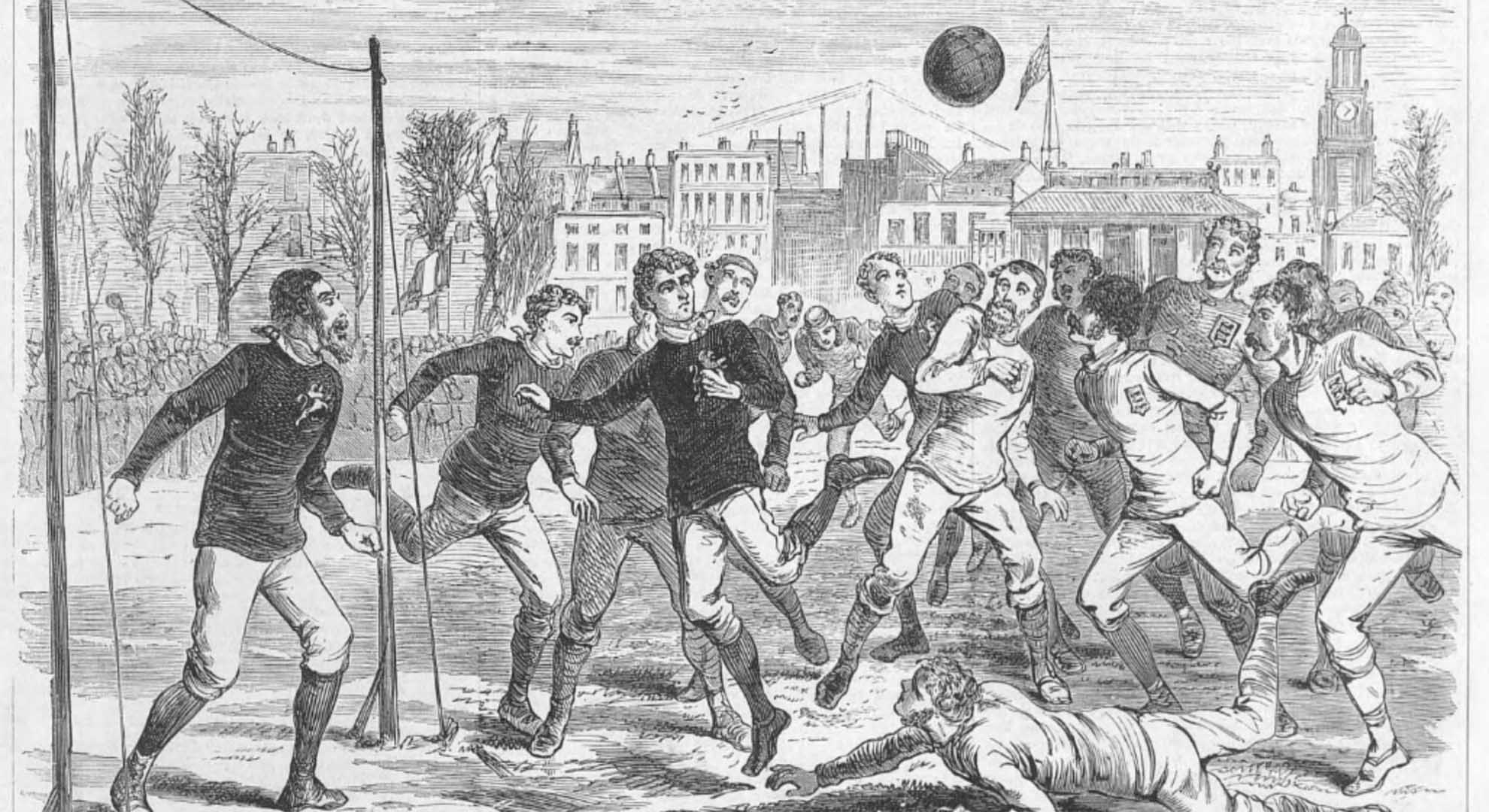

A recurrent theme among the histories of many individual sports from the mid-19th century to the present is the gradual standardization of fields of play by national and international governing bodies defining separate realms for players and spectators and demarking procedural rules. The football pitch exemplifies this pattern. From the 1860s to 1937, the regulation pitch evolved from a rectangular area of unspecified dimensions marked only by corner flags (some pitches in the 1870s were nearly twice the size of fields today) to its iconic configuration with well-defined boundaries and features such as the center circle and penalty areas.

While the pitch ideally is regarded as a constant, albeit with some variation of the dimensions and properties of the grass or artificial turf of the playing surface, players and coaches have dramatically transformed the way it is used. Jonathan Wilson’s book, Inverting the Pyramid (2008), succinctly traces more than a century of spatial invention from massed players dribbling the ball straight to goal favored by English teams in the late 19th century to spread-out attacking alignments utilizing the full expanse of the pitch. Today, we speak of players creating space with feints and moves that open distance between ball handler and defender, if only by a step, or of shutting down space by converging on the ball handler and closing off passing lanes.

In contrast to the anonymity of the football pitch, the distinctive features of golf courses—topographic variation, plantings, and even weather—are celebrated as constitutive elements of the game. Golfers play the course as well as their opponents. The familiar inventory of defined features including tee boxes, hazards, and greens, have been in place since the 1880s, but their specific forms and the overall dimensions of the course were then, as today, determined by the course designer’s subjective assessment of the degree of challenge and the aesthetic experience they offer players.

More than in most other sports, the design of golf courses, lends itself to the notion of authorship. The term “golf architect” referring to professional course designers became increasingly common in the 1920s. “The task of the architect,” H. N. Wethered and T. Simpson write in The Architectural Side of Golf (1929), “is therefore to create, if he can, this atmosphere of interest, to invent secrets that lie beneath the surface—even appearances that can be partly misleading … And with this concealment of the obvious there should be a feeling in all artificial construction for beauty of line and contour.” The golfer’s challenge is to solve the puzzles formulated by this conjuror, whose identity often contributes to the reputation of the course.

DOWNSLOPE APPROACH TO THE 10TH HOLE, ‘CAMELLIA,’ AT AUGUSTA NATIONAL GOLF CLUB, GEORGIA, USA, BOBBY JONES AND ALISTER MACKENZIE, ORIGINAL DESIGNERS, 1933. PHOTO: WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

Swedish artist Johan Ström’s Puckelboll (mogul ball) installations are spatial puzzles of a different sort. Conceived in 2002 and subsequently constructed in city parks in Malmö and suburban Stockholm with others under consideration elsewhere, the installations have the general shape and markings of a football pitch, but the familiar grass surface of the field of play is distorted by rises and dips recalling moguls on a ski slope, which redirect the path of the ball unexpectedly, and the goal posts have the twists and loops of soft licorice sticks. Ström implanted these quirks to challenge the conventions represented by regulation pitches and spur spontaneity in play. They dramatize the tension between constraint and freedom that is at the heart of the spatial practice of sport.

MAIN IMAGE: Puckelboll pitch in Malmö, Sweden, designed by Johan Ström, 2002. Photo: Wikimedia Commons