From Rockets to Rocks

How space culture influenced me as an architect

July 8, 2011 – Excitement is in the air. We are about to witness the last launch of Space Shuttle Atlantis for a new mission on space research. As the countdown approaches the final minute, anticipation swells. Energy is high, but I am feeling calm and confident. This is not my first shuttle launch.

Six seconds before the launch, the shuttle’s main engines ignite. This is a significant moment. While you cannot un-light the solid rocket boosters that do the heavy lifting, you can turn off these engines if something goes wrong. NASA has only six seconds to recognize something is not right before committing to lift-off. These engines are asymmetrically loaded, pushing the nose of the shuttle down. As it creaks forward, it is barely restrained by a handful of bolts to the launchpad. The astronauts on top are well aware of this un-natural motion. Those tiny bolts slow the shuttle’s forward fall, pulling it back to vertical just in time for launch. The solid rockets ignite.

Meanwhile, three miles away, we are cheering and screaming out the final countdown. As we reach zero, the sky glows with the burst of the rockets and a pool of smoke engulfs the shuttle. The shuttle appears to hover, but it soon accelerates faster and faster. Seconds later, a wall of sound washes over us. I am in a state of nostalgia, remembering this thrill from my childhood. But halfway up the sky, I am overcome by a contradictory feeling. I am no longer thinking as a spectator, but now as an empathetic and responsible adult. I cannot believe that humans are sitting on top of that bomb for a mission on space research. That… is reckless.

The culture of space exploration

It was not until this very moment that I realized my childhood was abnormal. Growing up with a parent as an astronaut, I was surrounded by other children whose parents were either also astronauts or worked for them, as their trainers, dentists or accountants. In that community, being an astronaut was certainly cool, but also very normal. It was our normal. I now live outside that community operating in a different discipline—design. I am struck by how the alien culture of that community has impacted my career.

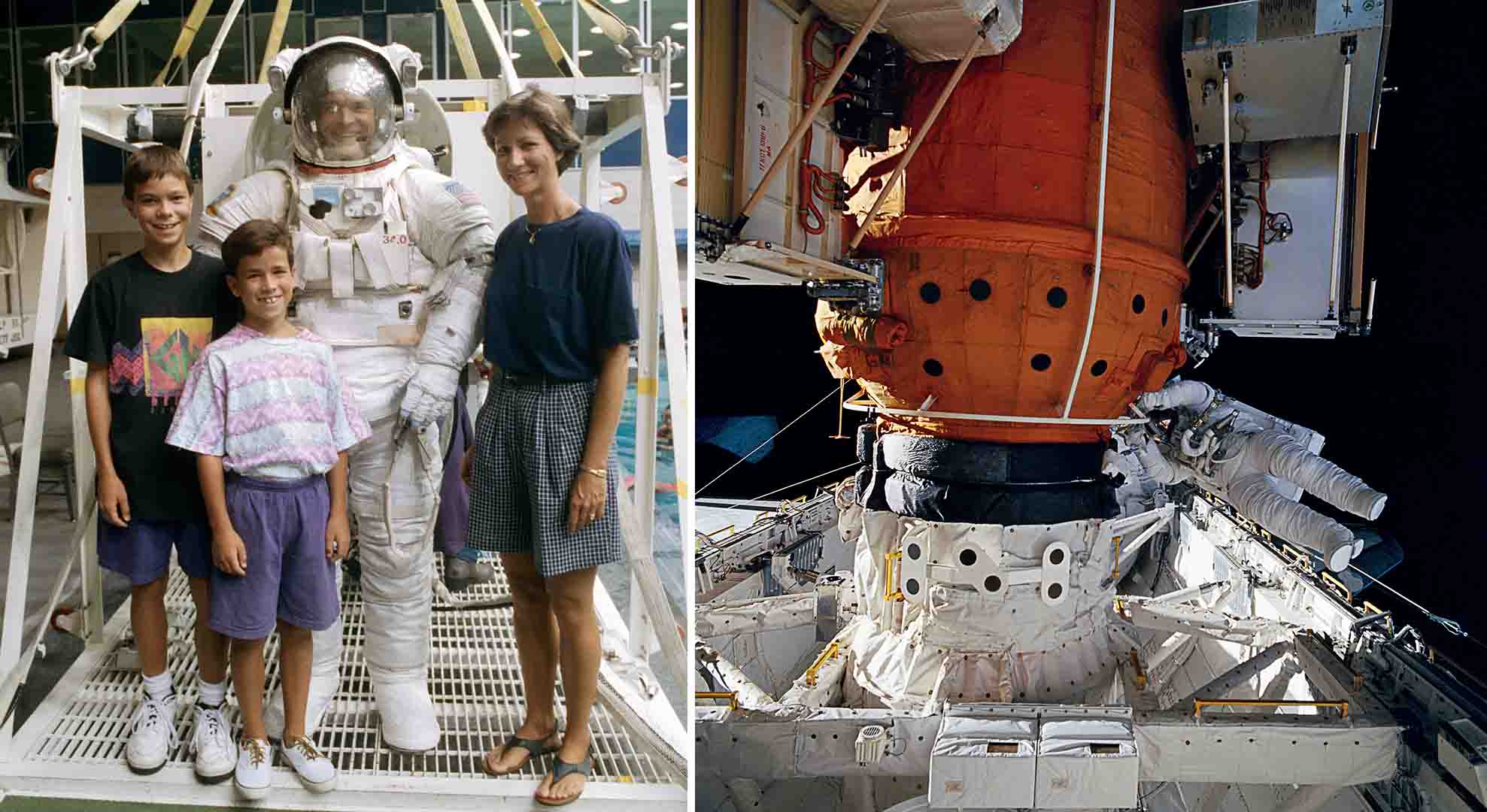

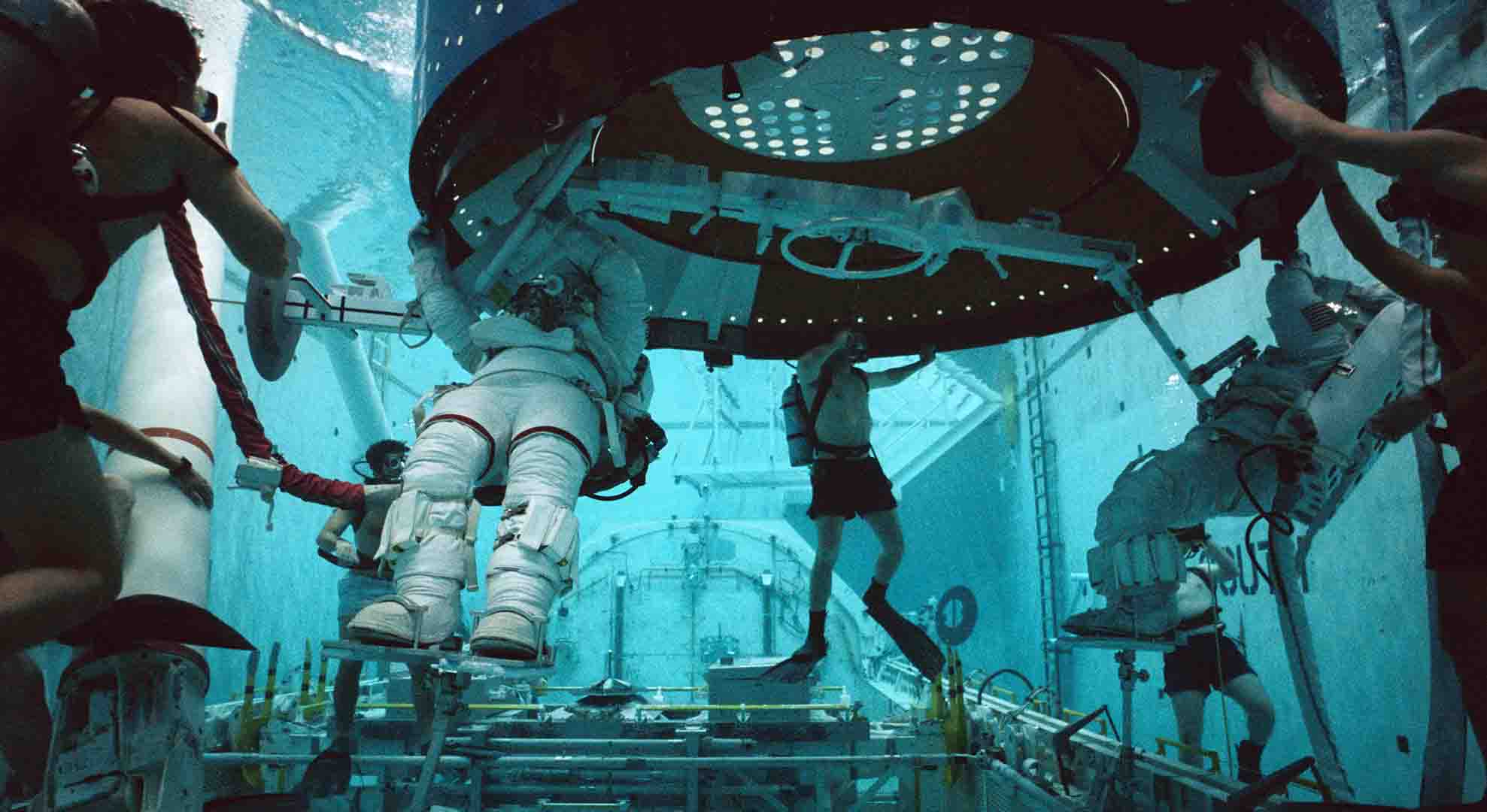

Rich Clifford in the WET F facility in Houston Texas during mission STS-49’s repairs of the Hubble Space Telescope in 1992. While astronauts in space recovered from an aborted repair, astronauts on the ground experimented in the Neutral Buoyancy of the WET F to test different methods of repair and report back to space with instructions. Photo ©NASA.

For example, you don’t often hear the word ‘safety’ in astronaut-talk. There is nothing safe about hurdling humans into outer space. If you evaluated space research and exploration based on safety, it would never happen. Instead, the concept of safety is replaced with measured calculations against risk. Another hefty portion of that culture surrounds spectacle. While the bones of space exploration are militaristic, scientific and engineered, the meat of their mission is to engage the public, captivate emotions, and build suspense. Conspiracy theories aside, it is undeniable that NASA devoted a healthy portion of its energy to putting on a show. These operations feel natural when you are raised inside them, but are now evidently unique to that culture.

“I have dropped the safe assumption that architecture is exclusively tied to buildings and am exploring the rituals and performances that surround the transportation and assembly of ancient wonders.”

From space-age to stone-age

The irony is not lost on me that while my father dedicated his life to exploring space at zero-gravity, I turned my attention to gravity-laden rocks. From space-age to stone-age. But really, what could be more alien to a space child from flat and swampy Clear Lake Texas than ancient megalithic stones? Looking at my work, there are certain values that were clearly defined by the particular context in which I was raised. My work is fueled by exploring the unknown in the pursuit of new knowledge, but I think at the core of both of our careers—mine and my father’s—is the pursuit of performing the impossible, whether it be exploring the vacuum of space or floating a stone. The more secure I feel in my career, the more risk I am willing to take. I have dropped the safe assumption that architecture is exclusively tied to buildings and am exploring the rituals and performances that surround the transportation and assembly of ancient wonders.

Imagine attending the assembly of Stonehenge, or witnessing the Moai stone heads being transported around Easter Island. Those were their shuttle-launches and space research; community driven moments of otherworldly experiences. Not only were those ancient megalithic sites spectacles in themselves, but they also constructed connections between humans and the cosmos. They recorded celestial events, gathered communities for memorials and projected predictions of the future.

While in my work I exercise the mysteries that surround old rocks, I have apparently never left the headspace of NASA. The space industry taught me to advance our knowledge by telling a story; to build a spectacle, a performance, and an impossible feat of strength to captivate the attention of an audience. It taught me that you can still pursue knowledge while having fun and putting on a show; that the purpose of an experiment is equally as important as the experience itself.

MAIN IMAGE: McKnelly Megalith by the Megalithic Robotics Studio, a course taught by Brandon Clifford at MIT in 2015. Photo ©Brandon Clifford.