Good Living

A regenerative approach towards a future-proof Brussels

Due to the crisis in material and energy resources, existing buildings must be understood as carbon repositories inherently offering a regenerative contribution. You don’t have to construct the most ecological building, as it is already there. Reusing and adapting what already exists in the built environment is the truly regenerative action in the twenty-first century.

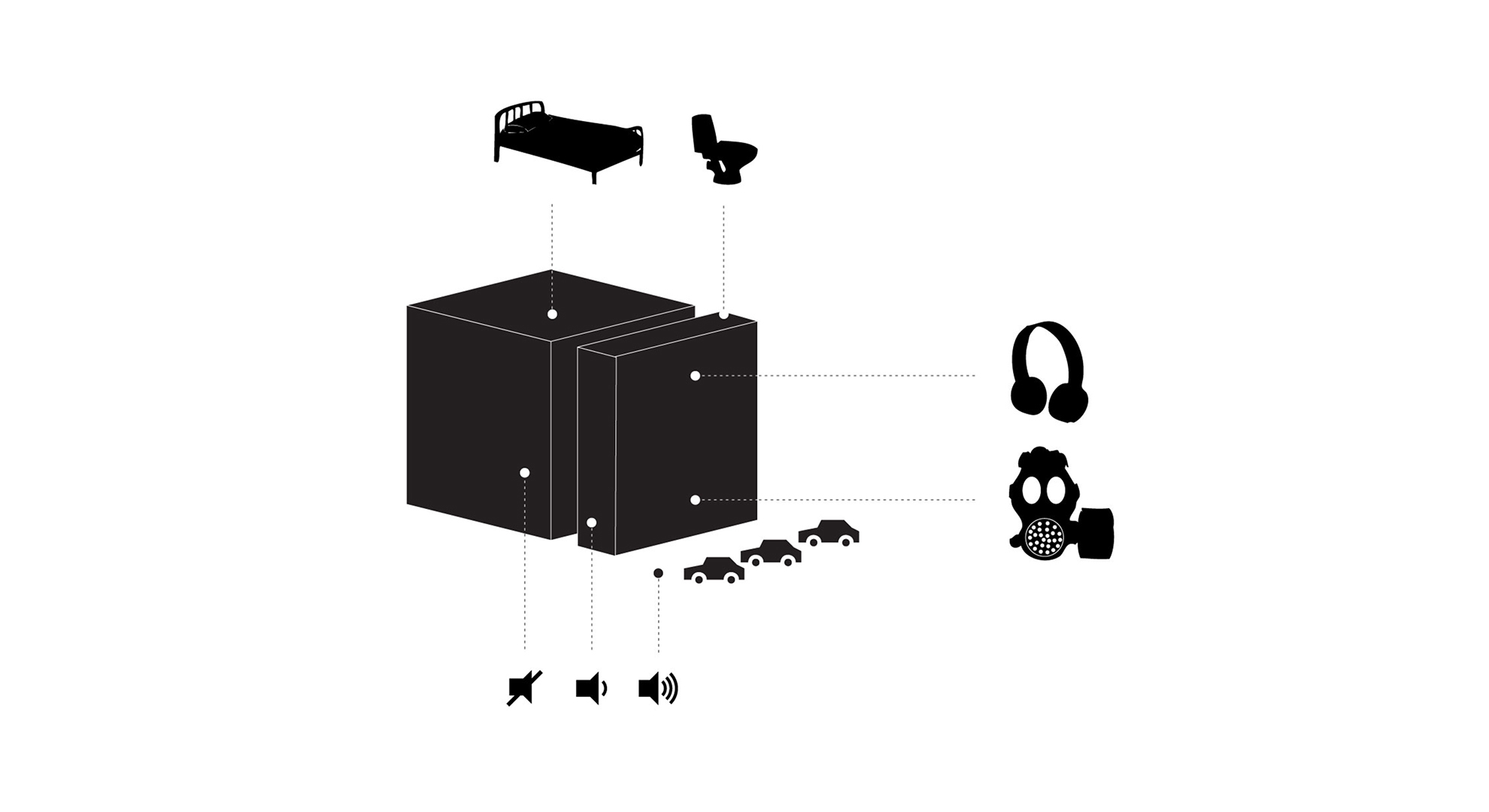

In office buildings constructed before the pressure of neoliberalism led to a reduction in clear height and circulation surface to maximize profits, there is often spatial generosity that allows great flexibility and invites architects to engage in a dialogue with the building, potentially leading to unconventional typologies. In 2012, our vision for the redevelopment of the EU Quarter included adapting and reusing vacant office buildings as housing. To mitigate traffic noise on Belliard Street, the main exit artery towards the airport and East Belgium, we thickened the existing facade to act as a sound barrier. Bathrooms, kitchens, dressing rooms—all shifted from the usual middle side of the dwelling to its perimeter.

Repurposing plan with thickened facade as sound barrier, EU Quarter Vision, Brussels, Belgium, 2012-14, &bogdan. Image © &bogdan

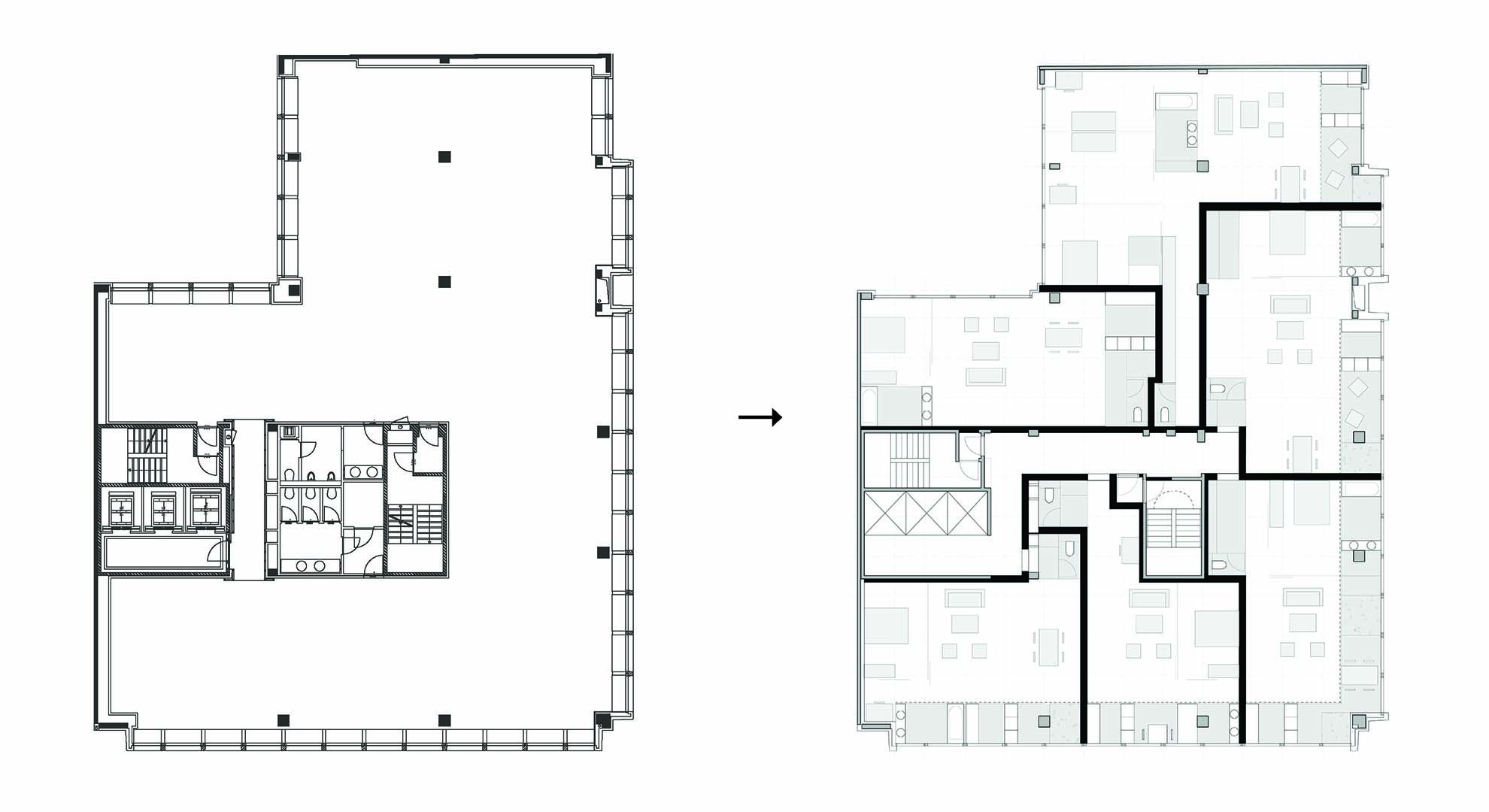

Infused with a second life, repurposed buildings tell stories and evoke a sense of surprise. This is evident in The Cosmopolitan, a 1960s high-rise office building standing perpendicular to the street as a rare insertion into the former Brussels’ trading port composed of late nineteenth century warehouses. Its significant volume and central location provided the real estate developer with the impetus to redevelop it into 130 dwellings with an exceptionally clear height of almost three meters and unique east and west views. This was in 2014, long before the adaptive reuse of office buildings established itself as a necessity. More than the living comfort, the immaterial heritage of this building—its history—is what sets it apart.

Before and after, adaptive reuse of an office building into housing, The Cosmopolitan, Brussels, Belgium, 2019, &bogdan. Photo © Jeroen Verrecht

When not operating in a historical center, where building heights are often reduced, adaptive reuse remains consistently more expensive than demolition-reconstruction. As long as the carbon footprint of existing structures is not integrated into the financial equation and the "polluter pays" principle is not applied, the limits of the current economic model are reached. A real estate developer cannot go much further in circular thinking, or they will be out of the market. It is thus crucial to establish a legal and financial framework that guarantees the best possible use of existing resources, including the buildings themselves.

In 2021, the Brussels-Capital Region government decided to do exactly this with its “Good Living” Building Code Reform. The Expert Committee entrusted with steering this reform advocates a shift from the current defensive Building Code to one that facilitates all present and future aspirations in the Brussels-Capital Region. This entails fostering innovative urban density, characterized by high-quality adapted and adaptable buildings, harmonized with increased open space and enhanced biodiversity—all while mitigating emissions from construction and building use. As per the revised Building Code, each project requiring a building permit must contribute regeneratively to the city as a whole, and consequently, a ban on demolition is being enforced. History indicates that the market self-regulates and property prices do not escalate with adaptive reuse, just as they don’t decrease with a reduction in minimum housing surfaces.

Concept for the adaptive reuse of office buildings, EU Quarter Vision, Brussels, Belgium, 2012-14, &bogdan. Image © &bogdan

The reform of the Brussels Building Code went even further in its commitment to regeneration by mandating that each permit application must demonstrate the feasibility of an alternative program or usage scenario. This measure is crucial in an economic landscape where real estate developers or buyers typically resist covering the additional costs of making a building conversion-ready. The next phase involves going beyond the Building Code’s reform to rethink fire norms and other regulations for adaptable buildings rather than specific programs.

Although not yet officially applicable, the “no demolition” objective of the Brussels Building Code has already been taken into account by public authorities. It has also inspired “HouseEurope!,” a citizens’ initiative advocating for EU legislation promoting the renovation of existing buildings and curbing demolition driven by speculation amid a widespread housing crisis in Europe. If one million signatures are collected, a debate on “HouseEurope!” will take place in the European Parliament building in Brussels, which, ironically, is a product of speculation.

Main image: A regenerative approach towards a future-proof Brussels, Brussels Building Code Reform, 2021-22. Image © &bogdan