Living in a Faraday Cage

Quiet time in an era of hyperconnectivity

It’s been a year of retreat. We are living in a time of enormous disruption in terms of how societies use and organize space. In many parts of the world we have been confined to our homes. In my home city of Melbourne, we endured a gruelling 112 day lockdown, which turned our sprawling, centralized city into a city of local villages. Strict curfews and travel limits were our new way of life while our once vibrant center became a ghost town. All of this has had an emotional impact on people, not just here, but all over the world, as countries raced to manage the impacts of the pandemic. For those of us who live in small apartments or alone, being confined to our homes was particularly difficult. Isolation and close confines became the norm.

Imagine if this pandemic had happened 20 or 30 years ago. The days when you watched movies after browsing up and down the aisles of your local video library. Being locked in your home forced to watch reruns of “The Price is Right,” with 56K dial up internet and the most rudimentary of web experiences. We often take for granted now that most of us carry a device in our pockets, that can literally access any bit of information created in human history—fast.

Our new “working from home” lifestyle has been made far easier by two simple factors: the accelerated technological advances of the last couple of decades, and the exponential increase in internet speed. The age of cloud computing and Zoom has made the sudden transformation to working from home for a huge number of workers a lot more straightforward than it would have been, and probably allowed more people to retain employment. It has also diversified communication channels, with some unintended consequences.

In the 1980s and 90s, most people would communicate instantly with those not around them via one channel: the telephone. You couldn’t tell who was calling, you just answered. If you didn’t want to talk, you could let it go to the answering machine. If you wanted to send any written communication, it was via post, or for faster communication, a fax. Few people had fax machines in their homes and no one ever expected an instant response as it was simply not possible. In public, at dinner or bars, you talked to people. It was easy to live in the moment.

Then we got email, instant messaging, SMS, social media, and what has become an explosion of communication apps for everything from dating to project management, to personal health and well-being. All made infinitely portable and omnipresent with the invention of the iPhone. There are literally thousands of channels for communication available now, connecting people all over the world. Whatever you’re into, there is a channel for it. It should be liberating, but things are never as they seem.

This narrowing of communication pathways, and lack of actual human contact in the space of these interactions leads to siloed viewpoints, confirmation bias, and a lack of empathy and tolerance to those with different views. What was supposed to bring us together has done the opposite, and ultimately lead to the amplification of ignorance, and the rise of the trolls. More alarmingly, deep work and focus are now rarely achieved, when there are so many things competing for time and demanding instant responses.

This technological revolution has other impacts on the spaces we occupy and how they are designed. In the online era, workplace and retail design are going through a great disruption, which has become more about blurring them into a hospitality model to entice consumers. Bad “cookie-cutter” retail does not work in the era of online shopping; and no one wants to work in a sea of workstations when they can work in the comfort of their own home.

However, I would argue that it is in our living spaces where the most significant effects of this transformation are felt. Our homes are now invaded by a range of digital tentacles, reaching into the most private of places. Although we are spending more time at home, we are also spending most of it looking at small screens, and whether for work or socializing, they are always there, and on.

Video meeting platforms have actually exacerbated this stress. When you talk to someone in person, you are subconsciously gauging their microexpressions and reactions—something that takes a great deal of additional effort on screen. Perhaps it’s the camera location, discouraging eye contact. Design presentations become very difficult in these environments, as it’s what people don’t say that tells you the story; it’s how their bodies and faces react that you actually read subliminally.

The antidote for this is the opposite of the current trend of more screens, more connectivity. We should be embracing the basics of great interior design: light, space, proportion and warmth. A Faraday cage of relaxation where your mind has a bit of space to wander or engage directly with others. Human needs haven’t really changed in the last 50 years, and perhaps our homes should be designed with those needs in mind, rather than the ever-present uptake of new things and technology for their own sake. Our real priority should be well-being, not adrenal fatigue.

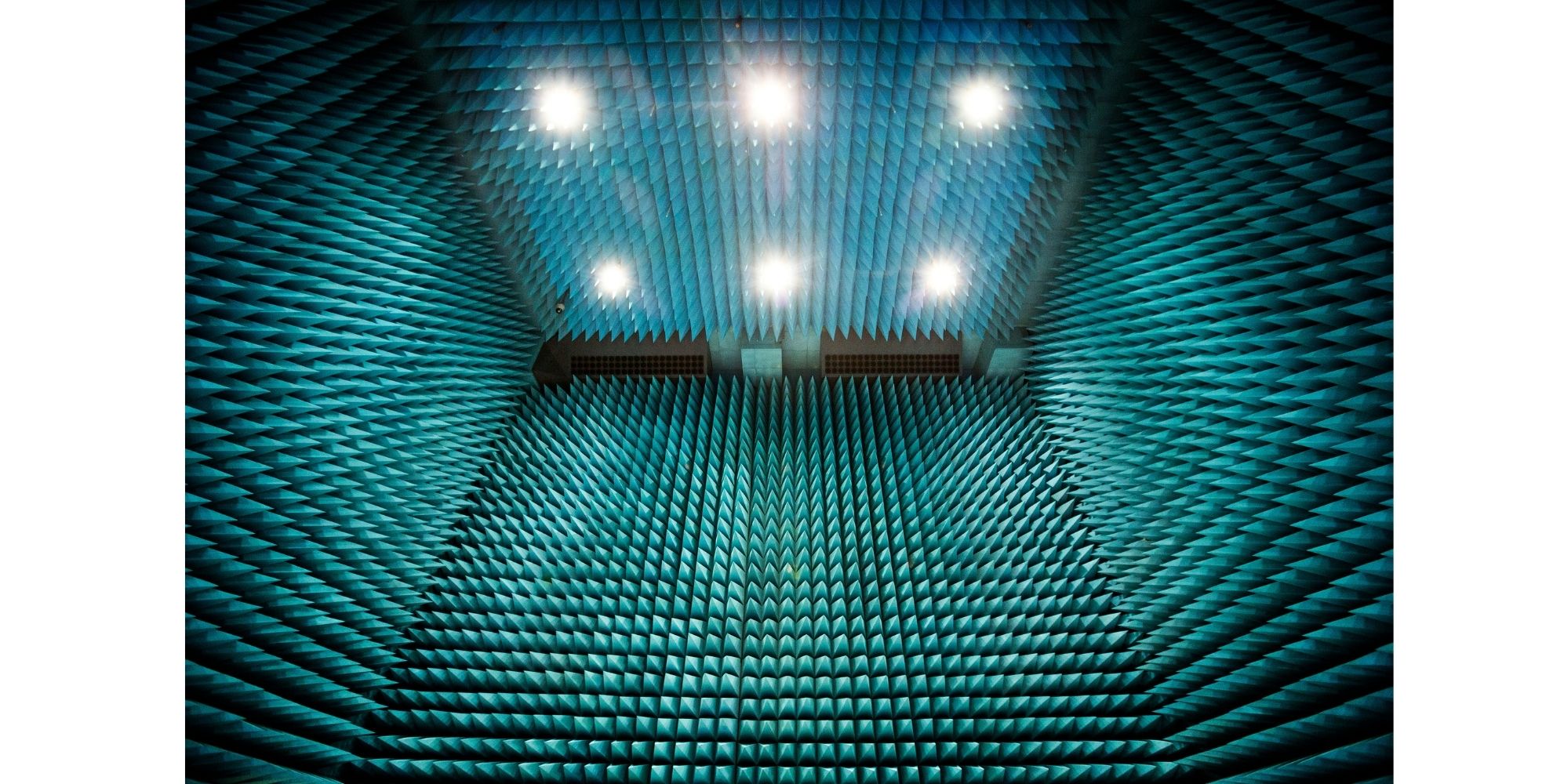

MAIN IMAGE: Interior of the Sarah & Sebastian store in Melbourne by Russell & George, “Even in the depth of the darkest oceans, some light always pierces through.” A quote by Naoshi Arakawa as inspiration for the design. Photo Sean Fennessey