Multispecies Materialities

Scaffolds for life and ecological kinship

“One way to live and die well as mortal critters in the Chthulucene is to join forces to reconstitute refuges, to make possible partial and robust biological-cultural-political-technological recuperation and recomposition….”

Donna Haraway, Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Plantationocene, Chthulucene: Making Kin

The notion of interspecies cohabitation may at first seem jarring and uncomfortable. Why would we want to share our living space with animals? Isn’t the point of architecture to provide humans with shelter from the “natural” world? The reality is, however, that this cohabitation already happens, whether we like it or not. Notwithstanding those humans who happily share their homes with domesticated pets, our architectures are rife with other living creatures, both visible and invisible. Recent studies have shown that humans share their homes with over 500 different species of arthropods alone; think of all the other critters, plants, molds, and microrganisms that inhabit the domestic ecosystem.

Custom molded rammed earth columns incorporate crevices and pockets for small mammals at the ground level, while supporting an elevated timber structure for humans to occupy above the ground. Project and images: Martin Hitch, Claire Leffler (Instructor: Adam Marcus)

Even closer to home, our own bodies in fact contain more nonhuman cells than human cells. At any given time, approximately 70 to 90 percent of the cells in our own bodies are fungal or bacterial—other organisms dwelling and thriving inside us. So, the real question is not if we should live with other species, but rather how we might embrace such coexistence and design our buildings to anticipate productive modes of interspecies cohabitation.

In recent years, a growing interest in designing for multiple species has emerged within the architectural discipline. Examples range from the speculative fictions of Design Earth and Fred Scharmen, which channel the rhetorical power of interspecies architecture to critique current environmental practices, to experimental installations by Ants of the Prairie, Terreform One, and EcoLogicStudio, which prototype new material strategies for promoting habitats for more-than-humans, to built projects by architects such as Atelier Bow-Wow and Bangkok Project Studio, which offer new models for humans and animals to share space.

Load-bearing gabion walls made of stacked rocks serve as primary structure for the building while also providing porous, damp habitats for local amphibian species. Project and images: Wan Yan (Instructor: Adam Marcus)

These diverse works are motivated broadly by a shared recognition that, as we grapple with the impacts of anthropogenic climate change, it is necessary to forge new models of collaboration and coexistence with the many other species with whom we share this planet. And while such sensibilities have been central to many Indigenous cultures around the world for millennia, the challenge for postindustrial society is now to unlearn many of our inherited assumptions about how architecture must serve as a protective bubble separating us from other species.

These ideas have been explored through a series of recent architectural design studios taught at the Architectural Ecologies Lab at California College of the Arts, in which students have collaborated to speculate on and prototype new architectural models for interspecies cohabitation. This work is sited in the dense suburban landscape of Fremont, California, a context of primarily single-family houses that follow suburban development logics now familiar in many parts of the world.

A complex timber structure fabricated from simple components provides dwelling and communal space for humans while sheltering subterranean habitats for burrowing owls. Project and images: Alden Gendreau, David Rico-Gomez (Instructor: Adam Marcus)

Originally the alluvial plain of the naturally flooding yet now channelized Alameda Creek, this landscape faces increasing challenges of habitat loss and decline in biodiversity. The studio work speculates on new forms of domestic architecture that test strategies for and pose important questions about cohabitation. How might biodiversity be reintroduced in productive ways? How can architecture encourage interspecies mutualism and cohabitation such that the greater ecosystem benefits? What opportunities might there be to rethink conventional models of domesticity premised on collectivity and care?

The focus of this design research is on material assemblies: Developing innovative approaches to conventional construction methods in ways that promote habitats for more-than-human species of plants and animals. These assemblies—timber frames that provide space for humans while protecting subterranean habitats for burrowing owls; gabion rock walls that support amphibian species; porous rammed earth walls with pockets for squirrels and other small mammals; armatures for hummingbirds; and mass timber roof systems with integrated planters for pollinator gardens—each respond to specific needs of local, native species while also structuring and organizing the spaces of the human domicile.

A cross-laminated timber roof system integrates planters with diverse plant species that attract and support local pollinators while also providing food for residents. Project and images: Suvin Choi, Wing Kiu Ho (Instructor: Adam Marcus)

The building envelope, traditionally thought of as an impermeable barrier between inside and outside, between humans and “nature,” is reimagined as a deeper, thicker, and more porous assemblage, actively negotiating the sometimes competing and conflicting demands of structure, enclosure, privacy, and habitat. It is in this negotiation that architecture’s most elemental purpose—as a boundary, a device of separation—transforms into one of connection, kinship, and ecological stewardship as the envelope becomes recast as a scaffold for multiple forms of life.

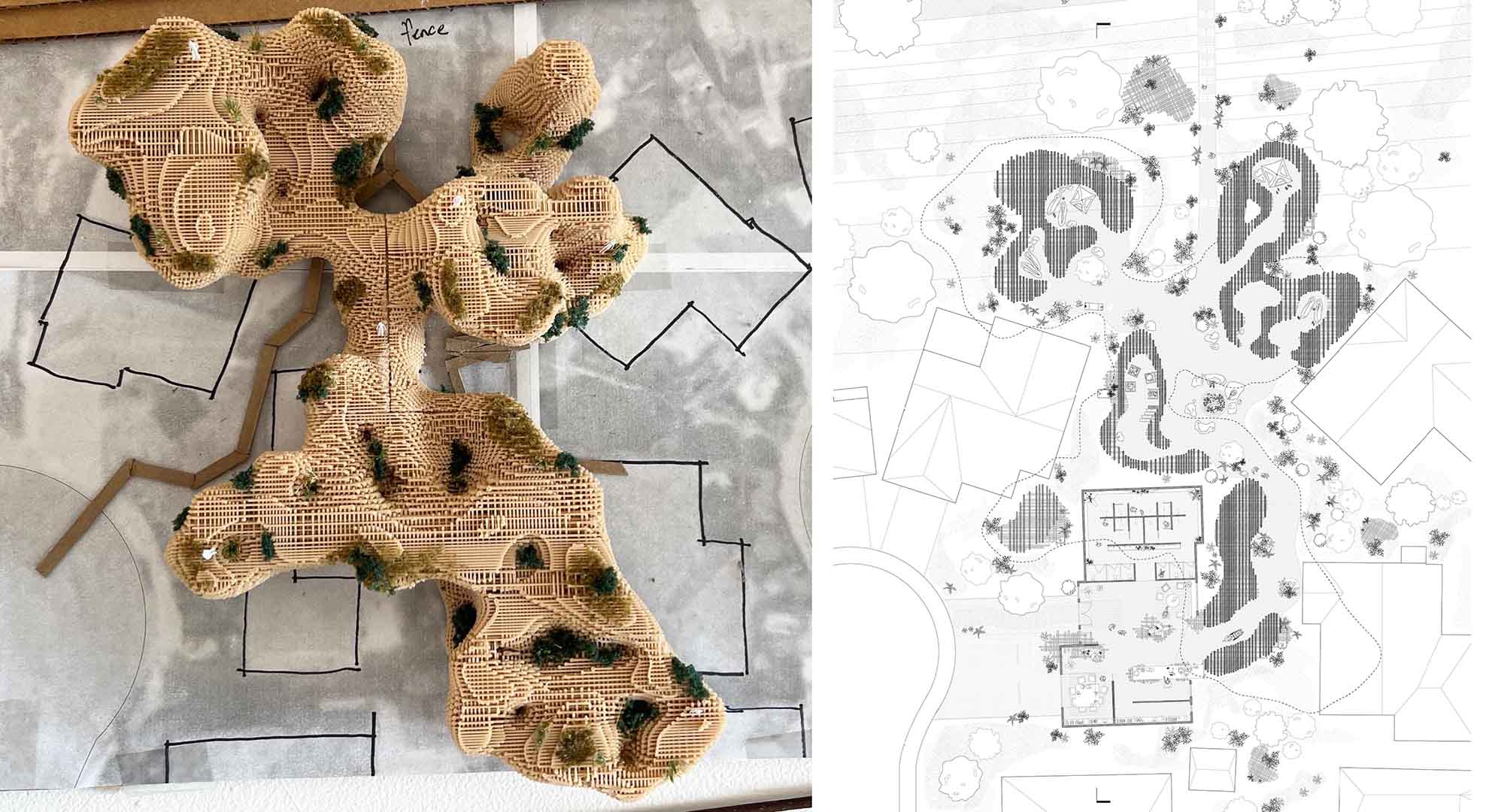

Main image: Monolithic rammed earth walls organize domestic spaces and degrees of privacy for residents, while also creating courtyards that are inaccessible to humans yet outfitted with timber scaffolds that support native hummingbird habitats.

Project and images: Kushaal Jhaveri, Amalia Pulgar (Instructor: Adam Marcus)