What was the Question?

Old and new trajectories in AI

Throughout history, the future has remained elusive, compelling humanity to continuously anticipate and strategize for the path ahead. In the attempt to read through all this uncertainty, every year the MIT Technology Review makes a list of four “premonitions” that will inform the forthcoming year of digital advancement, imagining how these will affect tech industries, the sociopolitical climate, information, and, yes, architecture. At the end of 2021, one of the breakthrough technologies listed was AI-produced images taking over in the architectural domain. And this was frighteningly accurate.

AI became popular and well known to nonprofessionals during the triennium 2020-23, when the American artificial intelligence company and research group OpenAI launched DALL-E and ChatGPT, two products that rapidly changed the way to craft images and articulate text. This has been massively used—and misused—in architecture, which has become a favorite playground to test AI-powered renders. It was an experiment that produced a few interesting results, but it also triggered an appetite for more substantial application of AI in the architectural field. Many questions arose regarding the benefits and the downsides of using AI in the design process, culminating in the recent survey by RIBA examining some key aspects of its use in practice.

ReSkin Series, scenario-based redesign of the facade of Biosphere 2. Image © Michela Falcone

Yet, as history tends to repeat itself, can we glean insights from the past to better comprehend what lies ahead?

The British architect, educator, influential writer, and maverick Cedric Price proposed the concept of the Fun Palace in the 1960s. With a great deal of irony, he used to provoke the audience of his lectures with the famous quote: “Technology is the answer, but what was the question?”

He envisioned the Fun Palace as a flexible and interactive cultural center that would serve as a catalyst for creativity and social interaction. Although it was never built, its principles have inspired generations of architects and designers, including those interested in the integration of AI into architecture. At its core, the Fun Palace was a radical separation from traditional notions of architecture and cultural institutions. Rather than a fixed and static building, Price conceived it as a "laboratory of fun" that could adapt and evolve to meet the changing needs and desires of its users.

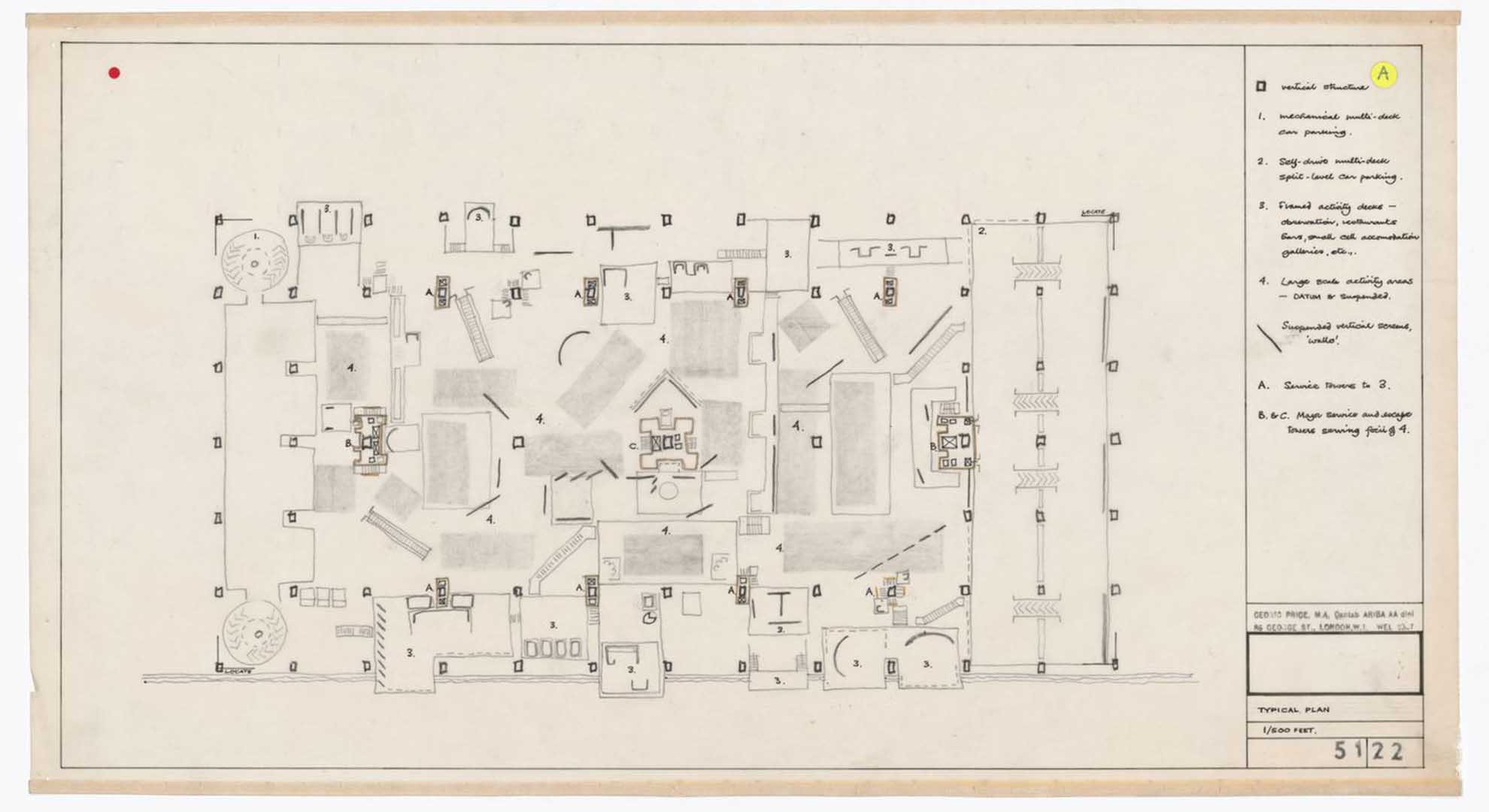

Diagrammatic plan, Fun Palace, 1963, Cedric Price. Image courtesy Canadian Centre for Architecture

The design was characterized by its flexibility, with movable and transformable elements that could be reconfigured to accommodate a wide range of activities and events. The concept of the Fun Palace becomes even more intriguing in the context of AI with its potential to enhance the adaptability and interactivity of architectural spaces, allowing them to respond intelligently to the needs and preferences of their users. Imagine a Fun Palace equipped with AI systems that can analyze user behavior, anticipate their needs, and dynamically adjust the environment to optimize their experience. This approach to design aligns closely with Price's vision of architecture as a process rather than a product, constantly evolving, iteration after iteration.

While the Fun Palace remains a visionary concept from the past, its principles continue to inspire contemporary architects and designers to explore new possibilities at the intersection of architecture and AI. The technology was not yet available, but Cedric Price had precisely described how this building could cybernetically calculate how to adapt based on users’ prompts.

Petting Zoo, Barbican Centre, London, 2014, Minimaforms. Photo © Minimaforms

In more recent years, there is another work that blurs the lines between technology, architecture, and human interaction. The Petting Zoo is an interactive installation designed by Minimaforms, the London-based practice of Stephen and Theodore Spyropoulos. At its core, the Petting Zoo is an experiment in creating a dynamic environment where visitors can engage with AI-driven robotic creatures in a playful and immersive setting. Central to the Petting Zoo experience are the AI-powered robotic entities, equipped with sensors that enable them to interact with visitors and each other in real time through touch, sound, and movement. AI ensures the robots a certain level of autonomy, allowing them to react, adapt, and behave in response to the environment and the people around them.

This project serves as a platform to explore ideas related to artificial life, emergent behavior, and the potential of AI to transform our built environment. By creating a space where humans and robots coexist and interact, Minimaforms challenges traditional notions of architecture and pushes the boundaries of what is possible in design and technology.

Petting Zoo, Barbican Centre, London, 2014, Minimaforms. Photo © Minimaforms

Cedric Price and Minimaforms, each in their own way, present pioneering approaches to incorporating AI into architecture. While Price focuses on prediction and Minimaforms emphasizes experimentation, both offer a framework in which AI serves as a tool and facilitator, enabling the creation of dynamic responses that adapt based on external feedback.

It’s undeniable that AI offers immense potential for innovation, but with the overabundance of options and information inundating us, there is a risk of losing sight of the original purpose. With no real agency in modifying or filtering these options, we constantly run the risk of forgetting what was the question.

Main image: Interior perspective, Fun Palace, 1964, Cedric Price. Image courtesy Canadian Centre for Architecture